|

CVS Plan to Limit the Dispensing of Opioids to One Week Supply

By James L. Holly, MD

In this review of CVS’ announced plans to further intrude into health care delivery, we will review:

My overall conclusion is that CVS’ effort to contribute to the abusive use of opioids is laudatory.

However, while it may be considered that CVS’ initiatives are healthy disruptive innovations in healthcare, there are serious questions about their violation of regulatory oversight involving their Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Company and their pharmacists in overstepping their professional boundaries in patient care? Historically, the ideal of pharmacists/healthcare provider collaboration was a team dialogue. CVS appears to want to eliminate the team and have the pharmacy benefits manager, pharmacy, pharmacists and CVS retail stores, with captive employed Nurse Practitioners, take over healthcare. The deficiency of the care which is being provided by CVS retail stores is obvious to everyone except CVS.

CVS is using their commercial enterprises to compete in a potentially monopolistic way with the primary care healthcare providers upon whom their commercial enterprises are dependent. It is possible that an organized effort on the part of physicians can direct their pharmaceutical business to other pharmacies which are not involved in competition with primary care providers.

This reaction can extend to primary care physicians who are involved in managed care organizations who use CVS Care Mart to demand that another PBM company be used. The very nature of illegal monopolies is that the size, influence and power of the perpetrator of the monopoly is insensitive to market demands. CVS’ size and profitability has them in that position presently but their leverage. At the very least every healthcare provider who is participating in a management care organization which contracts with a Pharmacy Benefits Manager should demand to know what utilization management tools are in place with the PBM which allows the physicians prescriptions and/or orders to be ignored without notification of or consultation with the healthcare provider.

The image of a retail pharmacy chain, through their extensive commercial enterprise and their powerful PBM, “taking over” healthcare is alarming to me. As a healthcare provider who is involved in primary care, in patient-centered medical home, and in managed care which contracts with CVS’ Care Mart, I argued for years that the Affordable Care Act did not intrude between the provider and the patient. What I did not recognize was that an intrusion had taken place and is expanding and it is through the collaboration between HMOs and PBM and the retail, commercial stores which are owned by a PBM.

At the least the following should happen:

- Every healthcare provider and particularly every primary healthcare provider should demand to know the policy of PBMs for changing a physician’s orders or prescription.

- CVS Care Mart must disclose its relationship with CVS’ extensive primary care network, particularly as to whether CVS NPs will be employed in the counseling of patients who come to the pharmacy but which are referred to the NP for education, counseling or changing of the primary physicians orders.

- All health plans should “opt out” of CVS Care Mart’s utilization management program which allows them to change physician orders or prescriptions without consultation with the physician.

- The recommendations made in the 8th installment of SETMA’s 2017 series on opioid abuse should be implemented. These can be read at: The Opioid Epidemic: Part VIII - What is the Solution.

On September 11, 2017, CVS announced a program which the company thinks will decrease the abuse of opioid medications. The following link describes their initiative: https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-health-fighting-national-opioid-abuse-epidemic-with-enterprise-initiatives. On September 21, 2017, Health Affairs published a blog written by three CVS’ CMO and two other CVS employees.

On September 23, 2017, SETMA’s CEO sent a letter to CVS’ CEO explaining our concerns about their plans. That letter, which has been published an open letter and which has been distributed to 105 pharmacies and over 500 healthcare leaders can be read at: CVS Plans to Change Prescriptions without Physician Approval - An Open Letter to CVS’ CEO. The following link is to the letter which accompanied the letter to pharmacies: Letter to 105 Pharmacies in our 5-county Area about CVS and Opioids.

On September 28, 2017, SETMA’s CEO received a response from CVS Care Mart’s CEO Larry Metro. The response came from CVS Health’s Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, Troyen A. Brennan, M.D., M.P.H. All of these materials are reviewed below.

In a private correspondence, and in the context of this conversation about CVS, PBMs and opioid abuse, an executive with a major healthcare accreditation agency said to me, “Their (CVS’s) playbook has definitely expanded. Years ago, Dr. Brennan came to the ACP and assured the leadership that CVS was not going to wade into ongoing primary care delivery.”

The following statement published by CVS demonstrates not only that CVS has not kept their promise but that the company now believes that they can offer better primary care than anyone else:

“CVS Health is a pharmacy innovation company helping people on their path to better health. Through its 9,700 retail locations, more than 1,100 walk-in medical clinics, a leading pharmacy benefits manager with nearly 90 million plan members, a dedicated senior pharmacy care business serving more than one million patients per year, expanding specialty pharmacy services, and a leading stand-alone Medicare Part D prescription drug plan, the company enables people, businesses and communities to manage health in more affordable and effective ways. This unique integrated model increases access to quality care, delivers better health outcomes and lowers overall health care costs. Find more information about how CVS Health is shaping the future of health at https://www.cvshealth.com.”

In the course of this discussion, I will argue that CVS’ providing of:

- retail pharmacy services,

- primary care services and

- pharmacy benefits management

Produces both a potential monopoly and certainly a conflict of interest between CVS and the primary care providers for whom they provide retail pharmacy services.

CVS’ intent for their cadre of Nurse Practitioners and Pharmacists to contact patients for whom they fill prescriptions without CVS possessing the patient’s medical records violates the spirit if not the letter of the medical practice acts of multiple states. If a healthcare provider writes a prescription for a patient without having seen that patient and/or without having a medical record of that patient, they will be found in violation of the medical records requirement of most states and very often will lose their prescribing habits.

Traditionally, pharmacies and pharmacists collaborated over pharmaceutical questions but now through their Pharmacy Benefit Management (PBM), CVS intends to direct the supply of medications through their retail pharmacy services. The potential harm of this initiative and particular its unlawful expansion of CVS’ pharmacy policy is alarming.

This material about Pharmacy Benefits Managers (PBM) was gleaned from a longer article posted on Wikipedia.

“In the United States, a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) is a third-party administrator (TPA) of prescription drug programs for commercial health plans, self-insured employer plans, Medicare Part D plans, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, and state government employee plans.

According to the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), "PBMs are primarily responsible for developing and maintaining the formulary, contracting with pharmacies, negotiating discounts and rebates with drug manufacturers, and processing and paying prescription drug claims. For the most part, they work with self-insured companies and government programs striving to maintain or reduce the pharmacy expenditures of the plan while concurrently trying to improve health care outcomes."

As of 2016, PBMs manage pharmacy benefits for 266 million Americans.[2] They operate inside of integrated healthcare systems (e.g., Kaiser or VA), as part of retail pharmacies (e.g., CVS Pharmacy or Rite-Aid), and as part of insurance companies (e.g., UnitedHealth Group).[1][5] There are fewer than 30 major PBM companies in this category in the US,[1] and three major PBMs comprise 78% of the market and cover 180 million enrollees.

Major PBMs

In 2015, the three largest public PBMs were Express Scripts, CVS Health (formerly CVS Caremark) and United Health/OptumRx/Catamaran.[17][18][19] In 2015, the largest private PBM was Prime Therapeutics, a PBM owned by and operated for a collection of state Blue Cross Blue Shield plans.

CVS Health

In 1994, CVS launched PharmaCare, a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) company providing a wide range of services to employers, managed care organizations, insurance companies, unions and government agencies. By 2002 CVS' specialty pharmacy ProCare, the "largest integrated retail/mail provider of specialty pharmacy services" in the United States, was consolidated with their pharmacy benefit management company, PharmaCare. Caremark Rx was founded as a unit of Baxter International and was spun off from Baxter in 1992 as a publicly traded company. In March 2007, Caremark merged with CVS Corporation to create CVS Caremark, later re-branded as CVS Health.

In 2011 Caremark Rx was the nation's second-largest PBM. Caremark Rx was subject to a class action lawsuit in Tennessee. The suit alleged that Caremark kept discounts from drug manufacturers instead of sharing them with member benefit plans, secretly negotiated rebates for drugs and kept the money, and provided plan members with more expensive drugs when less expensive alternatives were available. CVS Caremark paid $20 million to three states over fraud allegations.

Litigation about PBMs

In 2004, litigation added to the uncertainty about PBM practices. [27][40] In 2015, there were seven lawsuits against PBMs involving fraud, deception, or antitrust claims.

In 2011 a new division of the Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) was formed, with a mandate to license and regulate PBMs under the Mississippi Board of Pharmacy

State legislatures are using "transparency", "fiduciary", and "disclosure" provisions to improve the business practices of PBMs. The provisions require PBMs to disclose all rebate, discount, and revenue arrangements made with drug manufacturers, including all utilization information on covered individuals.

“Fiduciary duty provisions have stirred the most controversy. They require PBMs to act in the best interest of health plans in a way that conflicts with PBMs' role as the intermediary, which is the foundation of the PBM industry. The Pharmaceutical care management association, the national trade association representing PBMs, starkly opposes legislation of this kind. The PCMA believes public disclosure of confidential contract terms would damage competition and ultimately harm private and public sector consumers. The association also argues that transparency already exists for clients that structure contracts to best suit their needs, including imposing audit rights.

“Maine, South Dakota, and the District of Columbia have laws requiring PBM transparency. PCMA filed suit against Maine and the District of Columbia for their financial disclosure laws. In the Maine lawsuit, PCMA v. Rowe, PCMA alleged the law:

- Destroys the competitive market and will result in higher drug costs for Maine consumers

- Deprives PBMs of proprietary information and trade secrets

- Conflicts with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and the Federal Employees Health Benefit Act

- Violates the "taking and due process" clause of the U.S. and state constitutions

- Allows for broad enforcement of violation under the Maine Unfair Trade Practices Act

“PCMA won preliminary injunctions against the Maine law twice but was denied its motion for summary judgment. The judge agreed that financial disclosure was reasonable in relation to controlling the cost of prescription drugs. It was determined that the law was designed to create incentives within the market to curtail practices that are likely to unnecessarily increase costs without providing any corresponding benefit to those filling prescriptions. PCMA won an interim injunction against the D.C. law, with the judge ruling that it would be an "illegal taking" of private property.”

Dr. Holly’s Observations about PBMs

PBMs were created by market forces which required health plans to control their pharmacy costs. This need has become even more acute with the introduction of incredibly expensive pharmaceutics. The treatment of a single disease illustrates this point. Thus far 250,000 people have been treated with a drug for Hepatitis C. At a cost of $95,000 per patient, this represents an expenditure of over 2 billion dollars for the treatment of one disease. The Center for Disease Control estimates that between 800,000 and 1,400,000 people have untreated Hepatitis C. The majority of people who have this disease would expect Medicaid, Medicare or private insurance to pay the cost of their treatment.

Management of medication formularies, co-pays, medication costs, etc. are legitimate functions of PBMs. Never, however, was it ever expected that PBMs would begin to determine, as CVS’ Chief Medical Officer states below, that a PBM determine whether a medication is “clinically appropriate, (“In our role as a PBM, CVS Caremark implements UM programs for a variety of prescription drugs in order to ensure the medications are clinically appropriate…) That function is a clinical judgment based on a complete medical record which CVS does not possess. Additionally, while SETMA greatly respects nurse practitioners their prescriptive authority does not include opioids and in most, if not all states, pharmacists, whether employed by a PBM or a retail pharmacy does not have prescriptive authority either.

SETMA shares the alarm about the wide-spread use of opioids in the United States. Our objection to CVS’ plan does not come from a disagreement with their goal but only with their method. In addition to believing that their method is illegal in some states, abusive in the use of their PBM, a conflict of interest in that they are involved in Primary Health Care delivery, we believe that their method ultimately will be ineffective,

SETMA is a multi-specialty medical group which has used a robust electronic medical record since 1998. We have been awarded the HIMSS Davies Award, the Davies Peer Reviewed Stories of Success and Physician IT Leadership Award. We are the only practice to be accredited simultaneously for Patient-Center Medical Home (PC-MH) and Ambulatory Care by NCQA, AAAHC, URAC and Joint Commission (2010-2020).

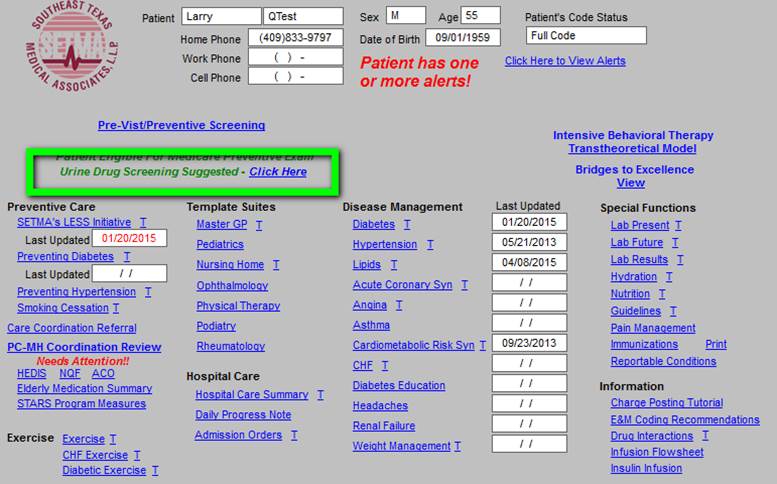

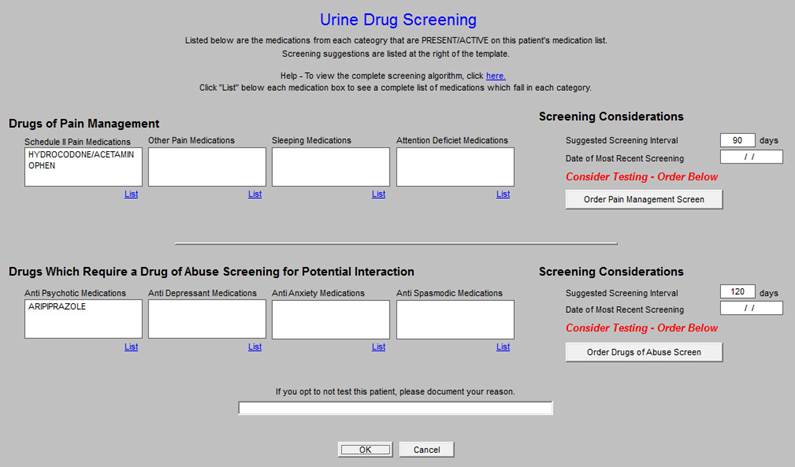

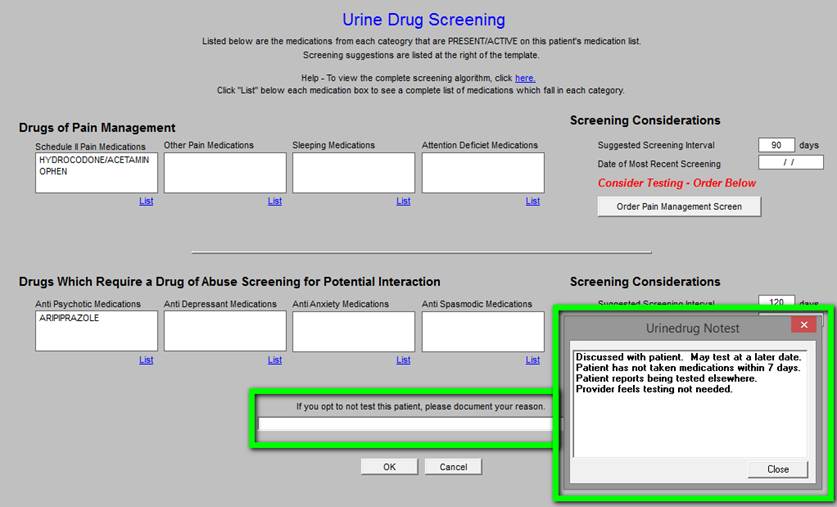

As a part of our efforts to prevent abuse of opioids, SETMA has created clinical decision support for Urine Drug Screens to Prevent Misdirection of Opioids and other Controlled Substances Prescribing Pain Medications: A Conundrum for Patient and Provider

SETMA’s examination of this problem was formalized in 2007 with a series of articles which can be read at SETMA.com: Prescription Drug Abuse Part I Introduction. (Note: see other articles link to this Part I at the end of the article) SETMA has published series of articles on opioids and other controlled substances use in 2015 and 2017. In the final installment of the 2017 series entitled: The Opioid Epidemic: Part VIII - What is the Solution which can be read at the following link: The Opioid Epidemic: Part VIII - What is the Solution. This articles states in part:

The following steps will start the stopping of the abuse of opioids:

With electronic prescribing, the monitoring of patterns of use of opioids is much easier.

All states must immediately require any prescriber of opioids to do so electronically. That will shut down pill mills very quickly. It will be objected to by providers who are not using electronic records or by providers who are using electronic records but are not e-prescribing controlled substances. These objections are not legitimate and should be ignored. If providers decide not to use electronic records and/or electronic prescribing of controlled substances, they should not be allowed to prescribe these drugs.

The patients’ medical records must reflect that:

- Before opioids are prescribed, except for five days following a procedure, that the patient has been tried on non-narcotic pain medication and/or on anti-inflammatory medications.

- The potential, and in the case of opioids, the certainty of physician or mental addiction has been discussed with the patient.

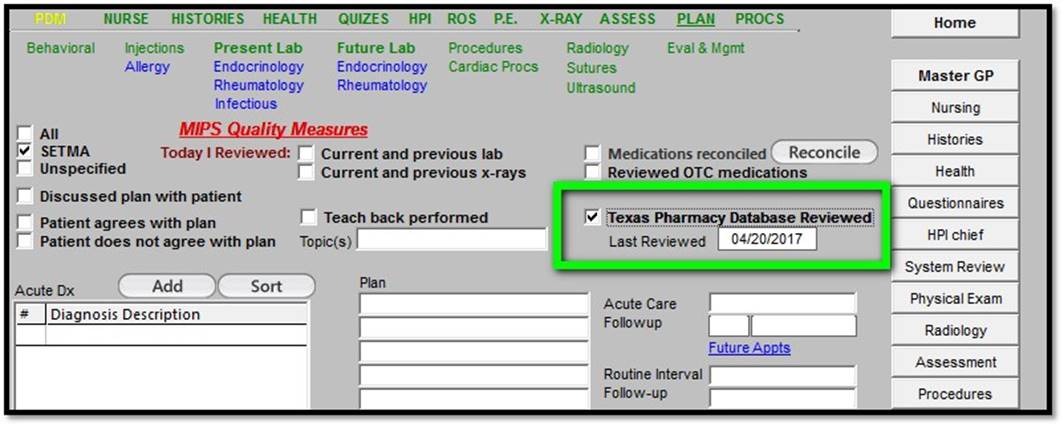

- At least once a year Prescription Access in Texas (PAT) must have been reviewed to see whether a patient is receiving controlled substances from more than one pharmacy or from more than one healthcare provider. The following is the way SETMA tracks this function in our EMR. EMR Screenshot

Texas Prescription Monitoring Program also called texaspatx.com - Prescription Access in Texas – this gives Texas Physicians the ability, at the point of care, to where patients are obtaining opioids or controlled substances. The following function is built into our EMR so that it is very easy for providers to determine if patients are obtaining these medications from multiple providers and/or multiple pharmacies

- A diagnosis or diagnoses is documented which warrants chronic pain medications

- An effort is made at least once a year to decrease the amount of pain medication being taken or to eliminate its use completely.

- If pain medication use is judged to be excessive, the patient is referred to a pain management specialist.

- Documentation of the use of a screening tool for patients who are high risk for abusing pain medications, such as the ‘Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain,” which is the tool which SETMA uses. This was discussed in last week’s article.

- All providers and pharmacies must be required to audit their own prescribing of opioids. Criteria for alerting potential abuse of opioids should be identified by an expert panel.

The following are suggestions for starting that process:

- Any patient on opioids longer than six months should trigger a requirement for a written review and justification by the provider, the patient and the pharmacy.

- Any patient taking more than three pain pills in a 24-hour period on a regular schedule.

- All opioids should be prescribed on an “as needed” or “prn” dosing schedule. This will not in and of itself stop opioid abuse but it begins to educate providers and patients that pain medications should be taken only for pain and not for the anticipation of pain or for the prevention of pain. The surest sign of inappropriate pain medication use is when a patient asks how many pain pills he/she takes in a day and the answer is, “It is prescribed for every four or for every six hours.”

- All of the following should trigger a review of a patient’s use of opioids:

- If a patient is taking more than one class or kind of pain medication simultaneously, a review should be triggered.

- If a patient is obtaining pain mediation from multiple providers, or from multiple pharmacies, a review should be triggered.

- Providers or pharmacies who prescribe or refill opioids for patients receiving them from multiple providers and/or from multiple pharmacies should lose their prescribing or dispensing privileges for one year for the first offense and permanently for the second.

If it is thought that these are draconian measures, it is consistent with the seriousness and severity of the problem. Administratively, this will be a night mare, but it would immediately be effective and it puts responsibility, functionally, where it will count. Also, these measures may seem intrusive but the crisis warrants such measures.

The following tool is used to identify patients who potentially are likely to abuse opioids. Tutorial for Individual Provider Assessing Patients Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP)

The following functionalities are a part of SETMA’s medication management:

- Electronic Medication Reconciliation through our EMR which is connected with the Sure Scripts Data Base for

- Electronic Medication Reconciliation

- In use since 2001, SETMA’s Pain Management Plan of Care: Pain Management Tutorial

Electronic Prescribing of Controlled Substances: ePrescribing of Controlled Substances Tutorial which includes urine drug screening to eliminate misdirection of prescribed medications.

This is only a brief introduction to SETMA’s efforts. In addition to demonstrating our commitment to the solving of this problem, it shows the inadequacy of CVS’ PBM and Walk-in Clinics approach to this problem. They can be a part of the solution, but they will not be THE solution.

On September 23, 2017, I wrote CVS’s CEO, Mr. Larry Merlo, expressing my concerns about CVS’ further intrusion into the practice of medicine through the use of its Pharmacy Management Benefits (PBM) program. The following link is to that letter: CVS Plans to Change Prescriptions without Physician Approval - An Open Letter to CVS’ CEO. This letter summarizes SETMA’s extensive clinical tools for supporting the appropriate and safe prescribing of opioid medications including the electronic prescribing of controlled substances.

On September 28, 2017, I received a response from CVS Care Mart’s CEO Larry Merlo. The response came from CVS Health’s Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, Troyen A. Brennan, M.D., M.P.H. The following is his response. My comments are in red for clarity. Following the review of Dr. Brennan’s letter to me, we will review his Health Affairs Blog, written by three CVS’ staff members and published on September 21, 2017.

“Dr. Holly, I have attached a response to your concerns you sent along to Larry Merlo. After you have had a look, and if you still have questions, please be in touch with me. Troy Brennan

As apparent from the material above, I have graver concerns than I had before about receiving this explanation of CVS’ plans.

“Dear Dr. Holly,

“Thank you for taking the time to share your views about our recent announcement regarding CVS Health’s initiatives to fight the national epidemic of opioid abuse. As a leader in pharmacy care, we are dedicated to helping the communities we serve respond to this growing public health crisis.

Two parts of this paragraph are bothersome. One is the use of the phrase, “epidemic of opioid abuse.” The word “epidemic” traditionally was applied to infectious diseases. It has been being applied to behavioral problems such as obesity and now to opioid abuse. In some ways, the solutions to the opioid problem are obscured by calling it an “epidemic” rather than acknowledging that it is a behavioral, addictive problem. In some ways this use of the word has become a function of “political correctness” which tends to diminish the individual responsibility for a problem of choice. One does not have to make a moral judgment about the behavior to acknowledge that it is a choice and to design a solution which includes personal responsibility.

The other problematical phrase in this paragraph is the term “pharmacy care.” This is a reflection of CVS Care Mart change of their name to “CVS Health,” which heralds the movement of CVS into the arena of Primary Care Healthcare Delivery and to the attempt to expand the role of pharmacists and pharmacies into the independent practice of healthcare.

“I think it is important to highlight that there are several components to our company’s efforts to help stem opioid abuse and misuse, including utilization management (UM) programs implemented through our pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), CVS Caremark, as well as education and support provided at our CVS Pharmacy retail locations.

CVS Health inappropriately expands their legitimate function by the using of the concept of “utilization management.” Though their PBM, CVS Health is attempting to go beyond legitimate UM -- management of medication price negotiations, formulary management and number of pills prescribed for a specific period of time, i.e. if a patient takes one pill a day and receives 90 pills, a refill will not be authorized for 90 day -- to a third party PBM such as CVS Health determining the appropriateness of medication prescribing and the PBM controlling of the number of pills issued with a lawful prescriptions for a different amount. This is a usurpation of a legal action by a licensed provider which usurpation is completed by a pharmacist or a PBM who does not have the legal authority to take that action and who does not consult with the provider who wrote the prescription.

“Per our announcement, our PBM, CVS Caremark, will enhance our approach to opioid utilization management for all commercial, health plan, employer and Medicaid PBM clients as of February 1, 2018, unless the client chooses to opt out. This UM program will include a seven day limit on the supply of opioids dispensed for certain acute prescriptions for new-to-therapy patients; a limit on the daily dosage of opioids dispensed, based on the strength of the opioid; and a requirement to use immediate-release formulations of opioids before dispensing extended-release opioids. These limits are aligned with the Guideline for opioid prescribing issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2016. With respect to the important role that the prescribing physician plays in the treatment of his or her patients, physicians are able to request an exception to the quantity limit based on their patient’s specific condition and medical need, as is possible with all of the treatment guidelines we implement through our PBM.

CVS’ “enhancement” of their approach to opioid “utilization management” goes beyond the legal authority of a pharmacist which is the only legal authority a commercial enterprise such as CVS Health can take.

In addition, CVS’ clever use of the “opt out” method makes it likely that most health plans will not recognize that to prevent CVS Health from taking this inappropriate and illegal action, the health plan must take the affirmative action of telling the PBM, i.e., CVS Health, that they are to act within the scope of their authority and not to take the proposed action. In most healthcare innovations, it has been determined that the “opt in” is the only legitimate course to take, but in that the actions proposed by CVS Health is inappropriate “opt in” or “opt out,” they are both equality inappropriate.

In the letter and Health Affairs blog below both of which are from the CVS Chief Medical Officer, it is candidly admited that the “opt out” choice is being chosen as the standard in the expectation that many health plans will do nothing which will allow CVS Health to initiate their inappropriate and illegal action.

Later, this review will examine the CDC “Guideline for Opioid Prescribing” in detail. There is no question that SETMA agrees with the guideline. The problem we have is whether or not a PBM such as CVS Care Mart (CVA Health) has the legal or moral authority to enforce the guidelines. We are confident that CVS does not.

The subtlety and the insidiousness of the last sentence of this section is alarming; it states, ”With respect to the important role that the prescribing physician plays in the treatment of his or her patients, physicians are able to request an exception to the quantity limit based on their patient’s specific condition and medical need, as is possible with all of the treatment guidelines we implement through our PBM.” The phrase, “the important role that the prescribing physician plays in the treatment,” drips with contempt by CVS for the legal ramification of healthcare professional licensure and privileges. Physicians, along with Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants play more than an “important role” in healthcare. They, in collaboration with patients and other members of the healthcare team including consulting pharmacists, play the key role. There is no role for CVS Health as a PBM in this process.

This last phrase of the above last sentence raises great alarms and motivates me to examine what other inappropriate utilization management strategies CVS Health has secretively or surreptitiously been employing in our patients’ healthcare decision making. The phrase states, “to the quantity limit based on their patient’s specific condition and medical need, as is possible with all of the treatment guidelines we implement through our PBM.” What other treatment guidelines has C VS Health implemented which allow pharmacists unilaterally to ignore physician orders?

“In our role as a PBM, CVS Caremark implements UM programs for a variety of prescription drugs in order to ensure the medications are clinically appropriate and cost effective. Given that this opioid UM program will be consistently executed as a coverage determination across all pharmacies in our PBM retail network, pharmacists at CVS Pharmacy, or any of the other retail pharmacies in our network, are not making independent medical judgments about the appropriateness of opioid prescribing or the length of such prescribing. Additionally, the program we have recently announced does not impact prescriptions filled for CVS Pharmacy retail customers who are not covered by the CVS Caremark PBM.

The following statement which leads this paragraph is loaded with implications which require examination. “In our role as a PBM, CVS Caremark implements UM programs for a variety of prescription drugs in order to ensure the medications are clinically appropriate and cost effective.” In that CVS Health justifies its proposed usurpation of legal actions by physicians with illegal actions by CVS Health based on prior actions which may or may not have been legitimate, but which are now explained as their PBM’s determination of the “clinically appropriateness” of other drugs, it is imperative that all health plans and physicians working with them immediately learn what patient care judgments CVS Health has been making.

CVS argues that this new opioid UM program,“…will be consistently executed as a coverage determination across all pharmacies in our PBM retail network…” In this statement CVS Health is being disingenuous. “A coverage determination,” means, one, that the drug is on the formulary and that if a three-month supply was issued three-months ago, a refill is covered.” The only legal “clinically appropriateness” which a PBM can enforce is that the patient has a diagnosis which supports the use of a medication. A pharmacist or a pharmacist organization (PBM) cannot legitimately question a diagnosis under it legal utilization management program.

“Separate from this UM program, our CVS Pharmacists will be strengthening counseling for all patients filling an opioid prescription in our stores, with a robust safe opioid use education program highlighting opioid safety and the dangers of addiction. This clinically-based program will help educate patients about the CDC Guideline, which advises the use of the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. Our pharmacists will also counsel patients about the risk of dependence and addiction tied to the duration of opioid use, the importance of keeping medications secure in the home, and how to properly dispose of unused medication. To further support these efforts, we will also expand our Medication Disposal for Safer Communities Program to include a total of 1,550 safe disposal units, 750 of which will be located in CVS Pharmacy stores across the country.

There are parts of this paragraph which are problematical but none which are objectively illegal or unethical.

“We recognize that there are patients with a legitimate need for pain medication, and our approach is carefully designed to ensure that those patients can access their medication in an appropriate manner. We are dedicated to ensuring our retail- and PBM-based approaches do not negatively affect patients who, for example, have cancer or palliative care needs, and are in need of their medication to manage chronic pain.

This is an appropriate caveat, if it is followed.

“Thank you again for taking the time to share your views and expertise.

“Regards, Troyen Brennan, MD”

Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, CVS Health

Dr. Brennan’s History

Troyen A. Brennan, M.D., M.P.H., is Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer of CVS Health. In this role, Brennan provides oversight for the development of CVS Health’s clinical and medical affairs and health care strategy.

Previously, Brennan was Chief Medical Officer of Aetna Inc. Prior to that; Brennan served as president of Brigham and Women's Physicians Organization. In his academic work, he was Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Law and Public Health at Harvard School of Public Health.

Brennan received his M.D. and M.P.H. degrees from Yale Medical School and his J.D. degree from Yale Law School. He has a master’s degree from Oxford University and earned a BS from Southern Methodist University. He completed his internship and residency in internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. He is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Pharmacy Benefit Management of Opioid Prescribing: The Role of Employers and Insurers”

Troyen Brennan, Richard Creager, and Jennifer M. Polinski

Health Affairs Blog September 21, 2017

In the last two decades, prescribing rates for opioids have increased nearly three-fold, from 76 million prescriptions in 1991 to approximately 207 million prescriptions in 2013. This remarkable volume of opioid prescribing is unique to the United States, where 2015 prescribing amounts were nearly four times those in Europe. Sadly, this much more frequent prescribing of addictive medications is connected to an epidemic of deaths related to abuse of opiates and other drugs of abuse. Drug overdose deaths are now considered a national emergency, topping 59,000 in 2016. The abuse of opioids can be seen as the leading public health emergency in the United States faces today.

I will not quibble with this statement but I would argue that access to care, affordability of care, alcohol addiction, murder rates among minorities, abuse and/or neglect of the elderly, disparities of care and child abuse and hunger are also leading public health emergencies in this country. If the authors said that the abuse of opioids is “a” leading public health emergency in the US,” it would solve this rhetorical deficiency in the blog.

The startling increase in the use of opioids has many causes. Two decades ago, health providers perceived that pain was under-treated, and in 1998 the Joint Commission formally recognized pain as the fifth vital sign. At the same time, drug companies developed and promoted a new generation of synthetic opioids, and added extended release as well as abuse deterrence formulations. Doctors prescribed, and patients consumed, these drugs in ever increasing quantities. At the same time, illicit forms of opioids became more widely available and abused. Now, with the harrowing increase in mortality attributed to opioid abuse, it is time to look for new solutions.

As the adverse consequences resulting from opioid misuse became apparent, employers sought the help of pharmacy benefit managers which responded by developing prospective (i.e., pre-dispensing) and retrospective utilization review programs to detect and intervene in unsafe prescribing of these addictive medications. Patients and prescribers who were engaged in unsafe behavior were identified and educated. Other interventions, in the form of member-specific drug limits, dispensing restricted to a single pharmacy, and prior authorization to ensure use for an appropriate diagnosis, were implemented – all programs shown to reduce opioid abuse. These programs had positive effects, but the magnitude of the opioid epidemic continued to increase.

Seems self contradictory! These judgment is that these measures helped but evidence is that “the magnitude of the opioid epidemic continued to increase.” None of these programs or processes interfered with the appropriate prescribing of medications but then CVS Health was not as brazen then as it has become since.

Additional Tools

Pharmacy benefit management companies have still more aggressive utilization management techniques to guide physician prescribing, including such tools as quantity limits, step therapy to emphasize generics and restricted formularies. We believe these can be used to bring about more appropriate use of opiates for pain management. However, some prescribers may resist embracing recommended guidelines to address this epidemic at the broad population-level. The American Medical Association (AMA) for example has criticized such programs as heavy-handed, cookie-cutter approaches, and has counseled that providers should be making these decisions on behalf of patients, taking into account individual patient needs. To be sure, prescriber autonomy and respect for the physician-patient relationship are of paramount importance. However, there is little evidence to show that past opioid prescribing habits are necessary or appropriate, and there is a great deal of evidence that they have produced significant harm.

I am not sure if I understand the last sentence in this paragraph. It appears to be rejecting the position of the AMA and physician-patient relationship or prescriber autonomy, but it is confusing. Perhaps the writers can explain what it means.

With widespread recognition that more aggressive control was called for, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assumed the lead, announcing a Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain in 2016. The CDC Guideline was based on three principles: opioids should be used only when necessary; only at the lowest dose and for the briefest duration needed; and when used, caution should be exercised and patients monitored closely. The Guideline made specific recommendations such as implementing step therapy requiring the use of immediate release formulations before extended release drugs when initiating treatment for chronic pain, avoiding doses greater than 90 Morphine Milligram Equivalents per day, and limiting prescriptions for acute pain to seven days or less. All of these recommendations can be integrated in standard utilization management.

It is no oversight that the CDC calls their proposal “Guidelines,” not “protocols.” The Agency for Healthcare and Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) published their National Guideline Clearinghouse which is described as “a public resource for summaries of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.” A “guideline” is an evidenced based recommendation, while a “protocol” is a rigid required step-by-step process analysis which must be followed.

What CVS Health calls “standard utilization management,” most physicians would call “practicing medicine.” My opinion is that the CDC Guideline should be implemented at the practice or provider level rather than at the PBM level. For physicians to monitor physicians and for physician committees to establish “step programs” would be appropriate. For PBMs to disguise their practice of medicine in UM vocabulary is not.

How would implementing such recommendations affect patients and their employers? We have used commercial insurance data to estimate the impact that imposing limits on daily dosing and length of therapy as outlined by the CDC could have on opiate addiction. The evidence suggests that in a given year, at a company with 100,000 employees, 61 employees would avoid addiction if prescriptions were reduced to align with the doses and duration of use consistent with the CDC Guideline. For employers, this translates into substantial health care cost savings, as a person struggling with addiction would have more than $15,000 in additional health care costs a year as compared to a person who is not dealing with substance abuse. Perhaps more important is the incalculable avoidance of human suffering—as certainly any employer would want to prevent the pain and suffering experienced by employees and family members who have lost loved ones to the consequences of addiction.

This paragraph is the most problematic from a science standard. The implementing of the recommendations in one practice will most often see patients just going to another practice where they can get what they want. The elimination of availability of medications at one venue has not resulted in a decrease in addiction. This is the most illogical paragraph in both Dr. Brennan’s letter to me and in the Health Affairs blog.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers’ Role

In the face of such a crisis however, we believe it is time to give greater weight to the CDC Guideline — based on patient care and safety. The CDC Guideline should become the default approach to prescribing opiates, a scenario in which physicians would have to seek exceptions for those patients who need more medication or longer duration of therapy. What is more, pharmacy benefit managers are better placed than others in the pharmacy supply chain to put this approach to the CDC Guideline into practice. Wholesalers have no real contact with patients or payers. Retail pharmacists have opportunities to provide patient counseling about opiates, and are required by the Controlled Substance Act to exercise a “corresponding responsibility” as to whether a prescription was issued for legitimate medical purpose. But when faced with a valid prescription written by a medical professional, it is difficult, and often not appropriate, for retail pharmacists to take it upon themselves to limit prescribing.

CVS Health is proposing the imposing of the CDC Guidelines in a coercive fashion by the PBM. This is consistent with the philosophy of many progressives and progressive organizations. It is not what the CDC Guidelines were intended, I think. If the CDC had proposed protocols, legislative or legal coercion may have been appropriate, but the CDC proposed “guidelines,” which are not compulsory.

PBMs have experience with implementing and enforcing such efforts. Their adjudication systems can enforce quantity limits (both strength and duration) as well as ensure implementation of appropriate step therapy of immediate release formulations before more dangerous extended release opioids are used. Currently, the major PBMs all offer such programs to employers or insurers who “opt in” to the program. Greater gains are possible if PBMs make such programs automatic or “opt out.” In this situation, clients would automatically have the limits built into their plan, unless they did not want them, and in standard PBM practice, few clients tend to opt out.

There is no correlation between the prescribing of an excessive dosage of a medication where an objective, evidenced-based standard exists in the medical literature and the refusal to fill a legal prescription by a legal provider. For instance, if a provider prescribes 160 mgs of Atorvastatin, it could legitimately be rejected as it is objectively a toxic dose.

That is not what CVS Health is proposing for opioids. CVS Health is declaring that in order to control the abuse of these medications, an obviously ineffective way will be employed, which supposedly will made successful simply by making it more difficult to obtain the opiods. That is UM gone amuck and it not a strategy which is likely to success. As evidence one simply has to see the extremes to which people are willing ot go to obtain illegal drugs, or to illegally obtain legal drugs.

In the end though, preventing opiate addictions and deaths are one of the core health benefits that payers, employers and insurers, should provide to employees and members. In light of the human suffering and financial costs caused by the current epidemic, a thoughtful, responsible, evidence-based treatment of pain is a service we must provide to our patients. Employing principles sanctioned by the CDC is clearly necessary and prudent

There is nothing in the CDC Guidelines which promotes for or allows pharmacists, or PBMs to violate the laws of the states in which they operate.

The statement which identifies “core health benefits that payers, employers and insurers…” shows the misplaced values of this effort to impose care upon people who don’t want care. Is this effort about public health or is it about profit of companies?

The bottom line for me in this entire discussion as a primary healthcare provider is that I want to continue to work every day, as I have for the past forty-four years, to help people make the right health care decisions, while being fully aware they have the right to make bad decisions. Ultimately, I have the responsibility not to facilitate, or to participate in their bad decisions.

Confronted with CVS Health’s proposal, many, if not most, people who are addicted to prescription drugs will make the same decision that one of my patients made years ago. When I saw her she was enormously overweight, at 5 feet tall, she weighed over 450 pounds. After a careful dietary history, I was convinced that she consuming about 1700 calories a day. I asked her, “Do you drink cokes?” She answered, “No,” to that and to tea. When I asked about coffee, she admitted that she drank over 40 cups of coffee a day. Before you express incredulity, I once had a patient in residency that drank five cases of beer a day.

When I asked what she put in her coffee, she said that she used two teaspoons of sugar and one tablespoon of fresh cow cream. I talked to her about changing her habits and offered help and encouragement. Pleased that I had practice good, patient-centered care, I was not surprised at her decision.

She changed doctors.

Compulsive and addictive behavior is compulsive and addictive. All the PBMs utilization management will not change that. Even compassion and counseling will not always change it.

|