|

Here is the List of 8 “Leftover 5” for your consideration:

SETMA believes that the key to the future of healthcare is an internalized ideal and a personal passion for excellence rather than reform which comes from external pressure. Transformation is self-sustaining, generative and creative. In this context, SETMA believes that efforts to transform healthcare may fail unless four strategies are employed, upon which SETMA depends in its transformative efforts:

- The methodology of healthcare must be electronic patient management.

- The content and standards of healthcare delivery must be evidenced-based medicine.

- The structure and organization of healthcare delivery must be patient-centered medical home.

- The payment methodology of healthcare delivery must be that of capitation with additional reimbursement for proved quality performance and cost savings.

The transition from volume-based reimbursement - a provider changing income by ordering more tests or doing more procedures - is very difficult without an external measure of quality which does not focus on “how much you do.” Capitation provides a routine and regular payment to the provider for the acceptance of responsibility to care for the patient.

Under capitation, there is no motivation for “doing more things” to and/or for the patient. Whether “the more” are frequency of visits or volume of testing or procedures, capitation does not drive the cost of care up. However, the limitation of capitation is that a provider may be tempted to not see the patient but to pass the patient off to specialists. Additionally, capitation may tempt providers to accept for treatment only relatively well patients who do not require a great deal of care.

Three modifiers can mitigate these risks. Theses modifiers can be used both to adjust the level of capitation and to provide value-based payments:

- The capitation payment should be adjusted by whether or not the provider and/or practice is accredited or recognized as a patient-centered medical home and/or by the level of accreditation which is held.

- Both the capitation and the value-based payment should be adjusted by standards of care and outcomes similar to the Medicare Advantage (MA) Stars standards and/or the ACO Quality Metrics. In that both of these are taken form HEDIS measures, they should be standardized and harmonized.

- Both the capitation and the value-based payments should be adjusted by the HCC/RxHCC coefficient scores similar to the MA, ACO and PC-MH use of these scores. (If you are not familiar with this category, it can be reviewed at the following link: http://jameslhollymd.com/epm-tools/tutorial-hcc-rxhcc-risk) This will reward a provider or practice for accepting responsibility for caring for sicker and more needy patients.

I don’t think so. Capitation imposes a discipline on the market If the capitation is not adequate - and historically insurance companies have wanted the capitation level to be very low, often to the point of stifling creativity - it can hurt practice development and transformation. If capitation is adequate, it does stabilize the cash flow of a practice and can therefore contribute to the sustainability of transformation

The elements and dynamic of patient-centered medical home promote value rather than volume. Patient activation, engagement, shared decision making, patient-centered conversations, etc. all promote the fulfillment of the Triple Aim as defined by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, which would be one very effective description and/or definition of value-based care.

The infrastructure of PC-MH and the elements of qualifying as a PC-MH all contribute to the performance of value-based healthcare. This is so much the case that in primary-care, I would recommend that qualifying as a PC-MH should be the first step in gaining value-based payments for care.

Yes. When using quality metrics endorsed by the National Qualify Forum (NQF), the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA, HEDIS metrics), Physician Collaborative for Performance Improvement (PC-PI), Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and others, all of which are evidenced based, peer reviewed metrics, providers are evaluating their performance by evidenced-based metrics.

At the core of the four principles identified in the second question above, SETMA"s belief and practice is that one or two quality metrics will have little impact upon the processes and outcomes of healthcare delivery and, they do little to reflect quality outcomes in healthcare delivery. In the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), healthcare providers are required to report on at least three quality metrics. This is a minimalist approach to providers quality reporting and is unlikely to change healthcare outcomes or quality. PQRS allows for the reporting of additional metrics and SETMA reports on 28 PQRS measures.

SETMA employs two definitions in our transformative approach to healthcare:

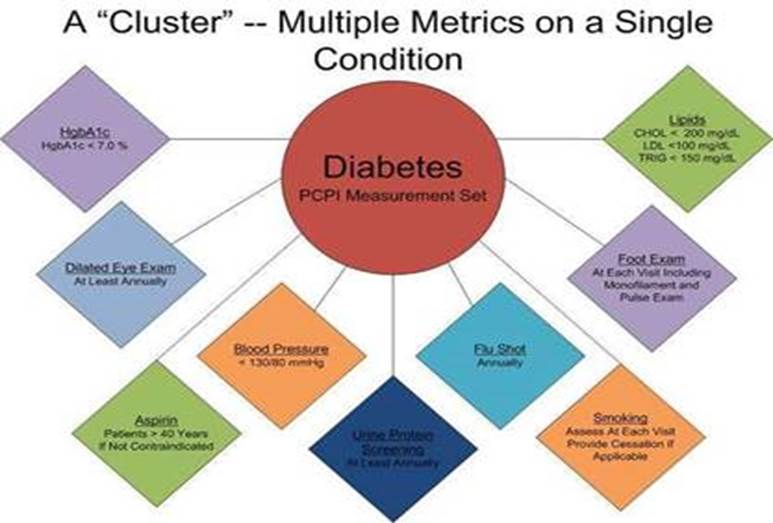

- A “cluster” is seven or more quality metrics for a single condition, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, etc.

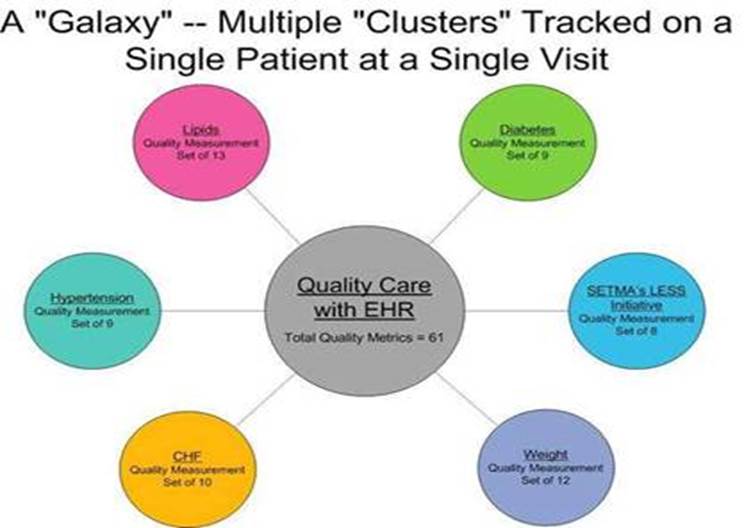

- A “galaxy” is multiple clusters for the same patient, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, lipids, CHF, etc.

SETMA believes that fulfilling a single or a few quality metrics does not change outcomes, but fulfilling “clusters” and “galaxies” of metrics, which are measurable at the point-of-care, can and will change outcomes. The following illustrates the principle of a “cluster” of quality metrics. A single patient, at a single visit, for a single condition, will have eight or more quality metrics fulfilled for a condition, which WILL change the outcome of that patient’s treatment.

The following illustrates a “galaxy” of quality metrics. A single patient, at a single visit, may multiple “clusters” surrounding multiple chronic conditions thus having 60 or more quality metrics fulfilled in his/her care, which WILL change the quality of outcomes and will result in the improvement of the patient’s health. And, because of the improvement in care and health, the cost of that patient’s care will decrease as well.

SETMA"s model of care is based on these four principles and the concepts of “clusters” and “galaxies” of quality metrics. Foundational to this concept is that the fulfillment of quality metrics is incidental to excellent care rather than being the intention of that care.

Quality Metrics Philosophy

SETMA's approach to quality metrics and public reporting is driven by these assumptions:

- Quality metrics are not an end in themselves. Optimal health at optimal cost is the goal of quality care.

- Quality metrics are simply “sign posts along the way.” They give directions to health. And the metrics are like a healthcare “Global Positioning Service”: it tells you where you want to be; where you are, and how to get from here to there.

- The auditing of quality metrics gives providers a coordinate of where they are in the care of a patient or a population of patients.

- Statistical analytics are like coordinates along the way to the destination of optimal health at optimal cost. Ultimately, the goal will be measured by the well-being of patients, butthe guide posts to that destination are given by the analysis of patient and patient- population data.

- There are different classes of quality metrics. No metric alone provides a granular portrait of the quality of care a patient receives, but all together, multiple sets of metrics can give an indication of whether the patient’s care is going in the right direction or not. Some of the categories of quality metrics are: access, outcome, patient experience, process, structure and costs of care.

- The collection of quality metrics should be incidental to the care patients are receiving and should not be the object of care. Consequently, the design of the data aggregation in the care process must be as non-intrusive as possible. Notwithstanding, the very act of collecting, aggregating and reporting data will tend to create a Hawthorne effect.

- The power of quality metrics, like the benefit of the GPS, is enhanced if the healthcare provider and the patient are able to know the coordinates while care is being received.

- Public reporting of quality metrics by provider name must not be a novelty in healthcare but must be the standard. Even with the acknowledgment of the Hawthorne effect, the improvement in healthcare outcomes achieved with public reporting is real.

- Quality metrics are not static. New research and improved models of care will require updating and modifying metrics.

“Mindset shift” is what Peter Senge in The fifth Disciple calls a “mental model,” which he defines as “deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations, or even pictures or images that influence how we understand the world and how we take action.” When the provider sees the goal as improvement in the health of the individual rather than in how many “things” we do to the patient, our focus will change - our mental image (mental model) will change.

Changing a mental model “...starts with turning the mirror inward; learning to unearth our internal pictures of the world, to bring them to the surface and hold them rigorously to scrutiny.” When we begin to see the patient’s welfare as the ideal rather than the financial well-being of the practice, we are changing our mental model of healthcare.

This “mind shift” or changing of our mental model “...also includes the ability to carry on ‘learningful’ conversations that balance inquiry and advocacy, where people expose their own thinking effectively and make that thinking open to the influence of others.” When this dynamic shift takes place, the financial success of the practice of medicine becomes a by-product of the Triple Aim - improvement in the patient’s experience of care, improvement in the patient’s health and the decreasing of the cost of care. The remarkable thing is that as this shift takes place, gradually and certainly the practice benefits financially but now incidental to excellence of care and not as the intention of the practice model.

It is the transition phase which will be “financial lean,” but once the transition is made, it is possible that with the lowering of cost due to the elimination of unnecessary and non-productive procedures, tests and services that the value-based payment model which will be less than the volume-based payment model may be balanced by the decreased cost of the value-based model.

Convincing healthcare providers to embrace value-based practice, particularly in the transition phrase may require an element of care-delivery reform - i.e., the imposing of regulations, restrictions, requirements, rules, etc -- as the mental model changes to where it is the internalized values of the provider which sustains this value transformation.

The structure for the reform which eventually can morph into transformation is already in place. Those who do not want to change their mental model and who choose not to participate in PQRS, PC-MH, MA or ACO can be penalized financially with their penalties being given to those who are going through this metamorphosis. By the way, that word is a transliteration of the Greek word μεταμόÏ?φωσις which means, "transformation, transforming.” It is use to address a fundamental change in nature unlike the Greek word METASCHEMATIZO which means just changing your appearance. Internally sustainable change in healthcare delivery will come from metamorphosis which is the result of transformation in healthcare delivery, whereas the externally change in appearance which requires external pressure to maintain the change is the result of metaschematizo.

This distinction is the “creative tension” which drives the transformation of healthcare delivery via the generative process of patient-centered care transformation and is the imperative for PC-MH being the hub of value-based payment reform. Encouraging physicians to embrace value-based payment reform is a function of shared vision, a change in philosophy and a renewed passion for the “profession” versus the business of healthcare.

|