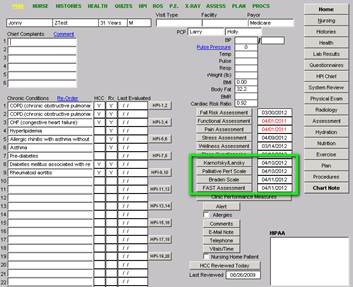

- Karnosky & Lansky Performance Scales

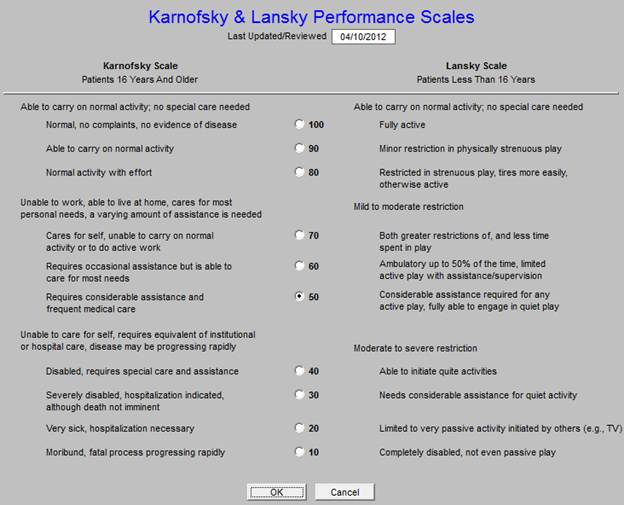

- Palliative Performance Scale for Cancer Patients

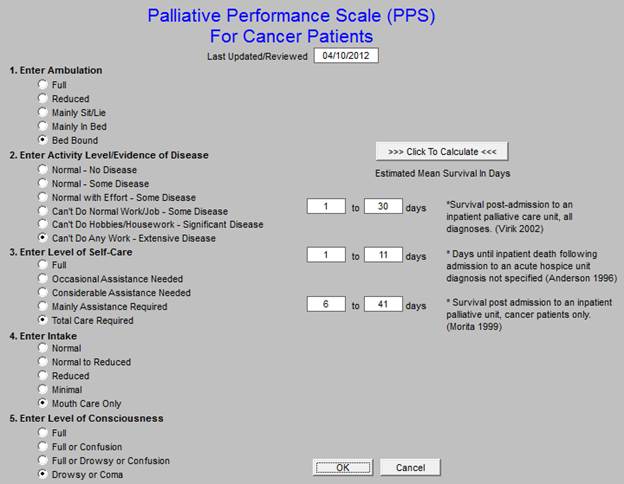

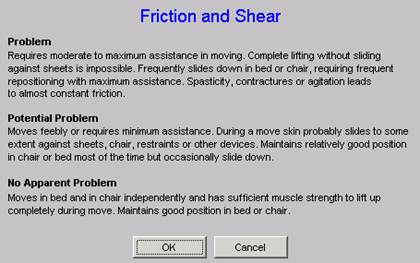

- Braden Scale Clinically Unavoidable Skin Lesions

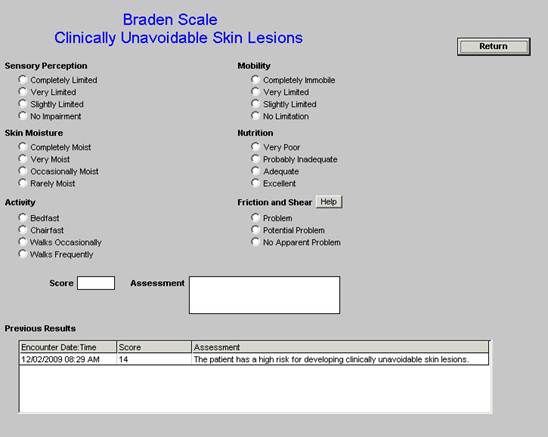

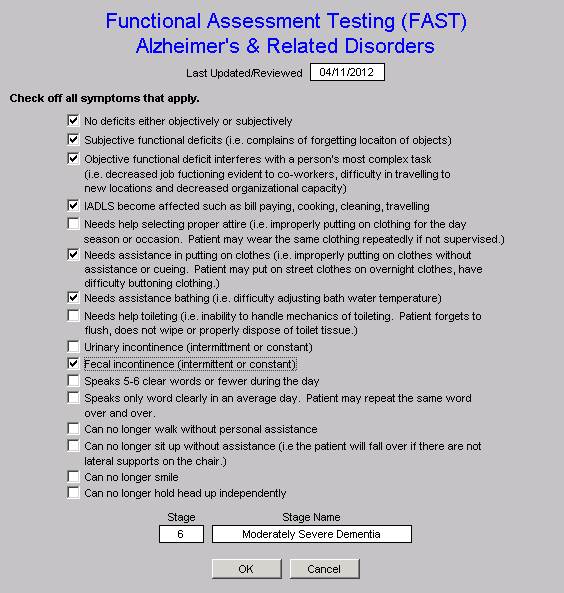

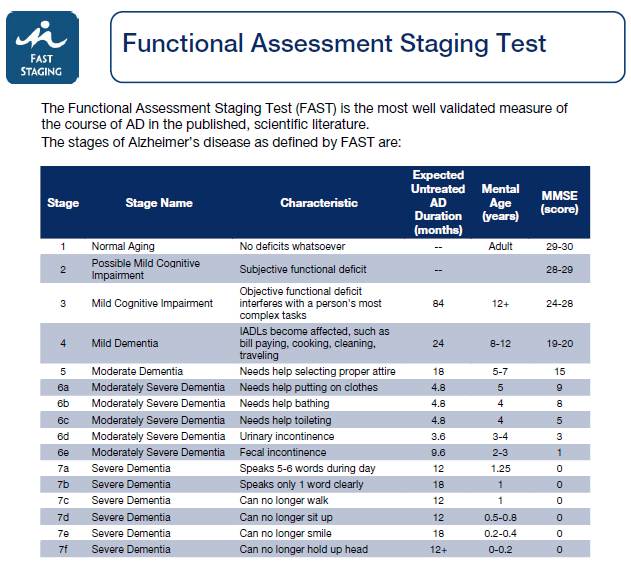

- Functional Assessment Testing Alzheimer’s and Related Conditions

As end-of-life planning becomes increasingly an important part of patient care, it is important to find ways of quantifying patient’s qualification for hospice care and where possible, a means of quantifying a reliable estimate of survival time for patients. While there will never be an absolute, four scores are being used to aid in this process. The first, the Karnofsky Scale, was first described in 1949; the second, the Palliative Performance Scale has been used in cancer patients since 1996; the third the Braden Clinically Unavoidable Skin lesions and the fourth Functional Assessment Testing Alzheimer’s and Related Conditions (FAST).

SETMA has deployed all four of these scores, along with a fifth which is the Lansky Scare. The Lansky is like the Karnosky Scale but is used with patient under 16. These tools can be found by going to GP Master Template. In the second column you will find these four scales. They are also deployed on the Master Template in the Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan Suite of templates.

These only need to be completed in patients you are considering referral to hospice care or palliative care. However, both the Karnofsky and the FAST have value in assessing those patients who are at high risk of readmission.

A Karnofsky score of 60 or less qualifies a patient for referral to hospice. Below, the SETMA’s EMR templates there are more details about both scales.

The Palliative Performance Scale for Cancer Patients is found on the same template. This score’s results are expressed in “survival time from the point of admission to hospice.” The evidence-based literature has only measured this scale in the case of patients with cancer. Further information is found below about this scale.

The Braden Score was developed in 1988 and has been used by SETMA in the Nursing Home patients since 2002. The Braden is based on 6 categories of evaluation and gives a score which indicates whether or not the patient is susceptible to clinically unavoidable skin lesions.

A tutorial for this assessment can be reviewed under Electronic Patient Management Tools: Nursing Home

The fourth tool is the Functional Assessment Testing (FAST) Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders. This tool is also valuable to use for cognitive functioning of patients with dementia but who are either not hospice eligible or not being considered for hospice.

- To be eligible for hospice beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease must have a FAST Scale of greater than or equal to 7 FAST Scale Items:

Stage 1: No difficulty, either subjectively or objectively

Stage 2: Complains of forgetting location of objects; subjective work difficulties

Stage 3: Decreased job functioning evident to coworkers; difficulty in traveling to new locations

Stage 4: Decreased ability to perform complex tasks (e.g., planning dinner for guests, handling finances)

Stage 5: Requires assistance in choosing proper clothing

Stage 6: Decreased ability to dress, bathe, and toilet independently;

Sub-stage 6a: Difficulty putting clothing on properly

Sub-stage 6b: Unable to bathe properly; may develop fear of bathing

Sub-stage 6c: Inability to handle mechanics of toileting (i.e., forgets to flush, does not wipe properly)

Sub-stage 6d: Urinary incontinence

Sub-stage 6e: Fecal incontinence

Stage 7: Loss of speech, locomotion, and consciousness:

Sub-stage 7a: Ability to speak limited (1 to 5 words a day)

Sub-stage 7b: All intelligible vocabulary lost

Sub-stage 7c: Non-ambulatory

Sub-stage 7d: Unable to sit up independently

Sub-stage 7e: Unable to smile

Sub-stage 7f: Unable to hold head up

- Documentation of specific secondary conditions (i.e. Pressure Ulcers, UTI, Dysphagia, Aspiration Pneumonia) related to Alzheimer’s Disease will support eligibility for hospice care.

Details of the Karnofsky Score Performance Status

The Karnofsky Score may be requested under certain diagnoses.

Breast cancer

Progressive disease

- Worsening clinical signs €“ see below

- Worsening lab values

- Decreasing functional status

- Evidence of metastatic disease

Clinical signs

- Pain, nausea or vomiting

- Thrombosis or DIC

- Bone marrow involvement requiring transfusion

- Superior vena cava syndrome

Disease stage

- Stage IV (any T, any N, M1) at presentation

- Progression of any earlier stage of disease to metastatic with either of the following:

- Patient continues to decline in spite of definitive therapy

- Patient refuses further treatment

Performance status

Dementia

Must have 2 of the following

- Ability to speak is limited to 6 words or fewer

- Ambulatory ability is lost

- Cannot sit up without assistance

- Loss of ability to smile

- Cannot hold up head

Patient should show all of the following characteristics

- Inability to ambulate independently

- Unable to dress without assistance

- Unable to bathe properly

- Incontinence of urine and stool

- Unable to speak or communicate meaningfully

Failure to thrive/debility

Clinical signs

- Progression of disease documented by symptoms or test results

- Decline in Karnofsky score

- Weight loss supported by decreasing albumin or cholesterol

- Dependence with 2 or more of the following:

- Feeding

- Ambulation

- Continence

- Transfers

- Bathing and dressing

- Dysphagia leading to inadequate nutritional intake or recurrent aspiration

- Increasing emergency visits, hospitalizations, or MD follow-ups related to their primary medical diagnosis

- A score of 6 or 7 in the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST) for dementia

- Progressive stage 3-4 pressure ulcers in spite of care

Heart disease

Clinical signs

- Signs and symptoms of CHF at rest

- Optimal dose of diuretic and vasodilator therapy

- Ejection fraction of 20% or less

- Cardiac symptoms:

- Arrhythmias resistant to therapy

- History of cardiac arrest

- History of syncope

- Cardiogenic brain embolism

liver disease

- Cirrhosis/hepatic failure - not a candidate for liver transplant

- Ascites refractory to medical management (Dietary sodium restriction and diuretics)

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Oliguria

- Urine Na < 10 mEq/L

- Elevated BUN/creatinine

- Hepatic encephalopathy refractory to medical management

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Recurrent variceal bleeding/spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Lung cancer

Progressive disease

- Worsening clinical signs €“ see below

- Worsening lab values

- Decreasing functional status

- Evidence of metastatic disease, especially brain

Clinical signs

- Pain, nausea or vomiting

- Dyspnea

- Significant hemoptysis

- Superior vena cava syndrome

- Recurrent pneumonia

- Pericardial effusion/pleural effusion

- Any metastasis

Disease stage

- Stage IV (any T, any N, M1) at initial diagnosis

- Stage III disease with pleural effusion

- A patient with stage III disease who continues to decline in spite of therapy, or refuses therapy

- Performance status Karnofsky score of 70% or less

Prostate cancer

Progressive disease

- Worsening clinical signs €“ see below

- Decreasing functional status

- Evidence of metastatic disease

Clinical signs

- Pain, nausea or vomiting

- Thrombosis or DIC

- Bone marrow involvement requiring transfusion

Disease stage

- Stage IV (any T,N,or M1) at initial diagnosis

- Progression of an earlier stage of disease with either of the following:

- Patient continues to decline despite definitive therapy

- The patient is refractory or refuses further treatment

Performance status

Pulmonary disease

Clinical signs

- Progression of disease documented by any of these symptoms:

- Dyspnea at rest

- Dyspnea on exertion

- Homebound/chairbound

- Oxygen dependent

- Copius/purulent sputum

- Cyanosis: fingertips, lips

- Barrel chested

- Poor response to bronchodilators

Functional status

- Decline in Karnofsky score

- Increased hospitalizations for pulmonary infections

- Decrease in FEV1 on serial testing of greater than 40 ml/year

- Hypoxemia at rest on supplemental oxygen

- Unintentional weight loss in the past 6 months

- Resting tachycardia (more than 100 per minute)

Renal disease

Clinical signs

- Uremia: clinical signs of renal failure:

- Confusion, obtundation

- Intractable nausea and vomiting

- Generalized pruritus

- Restlessness

- Oliguria: urine output of less than 400 cc/24 hours

- Intractable hyperkalemia: persistent serum potassium more than 7.0 not responsive to medical treatment

- Uremic pericarditis

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Intractable fluid overload

Laboratory criteria

- Creatinine clearance of less than 10 cc/minute

- Serum creatinine of more than 8.0 mg/dl

Stroke and coma

Clinical/functional status

- A continuous decline in clinical or functional status means the patient's prognosis is poor acute phase patients

- Comatose state lasting more than 3 days

- Comatose patients with any 4 of the following on day 3 of a stroke have 97% mortality by 2 months:

- Abnormal brain stem response

- Absent verbal response

- No response to pain

- Serum creatinine of more 1.5 mg/dl

- Age 70 or more

- Dysphagia severe enough to prevent them from receiving food or fluids

All other conditions

- The patient has a life-limiting condition

- The patient and family have been informed that the condition is life-limiting

- There is documentation of clinical progression of the disease

- serial physician assessment

- laboratory studies

- radiologic or other studies

- multiple ER visits

- inpatient hospitalizations

- home health nursing assessment if patient is homebound

- There's a recent decline in functional status, such as:

- requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care

- is disabled, requires special care and assistance, is unable to care for self, disease may be progressing rapidly

- Severely disabled, although death is not imminent

- Very sick, active supportive treatment is necessary

- Moribund, fatal processes progressing rapidly

and/or

- Patient is dependent in at least 3 of these activities: bathing, dressing, feeding, transfers, continence of urine and stool, ambulation to bathroom

and/or

- recent impaired nutritional status, as evidenced by unintentional, progressive weight loss of 10% over past six months, or serum albumin less than 2.5 gh/dl (may be helpful prognostic indicator but should not be used by itself)

The Palliative Performance Scale for Cancer Patients

“Accurate prognostication of the trajectory of an illness provides multiple benefits in end-of-life care. Prognostic information facilitates more realistic decision making regarding ongoing treatment, fosters risk-benefit considerations of specific interventions, and contributes to appropriate utilization of health care services. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) has been used as a tool for measurement of functional status in palliative care. This study explores the application of the PPS as a tool for projecting length of stay until death or discharge in a home-based hospice program.

PPS scores were associated with length of survival. Negative-change scores were predictive of patient decline toward death, while stable PPS ratings over time resulted in discharge consideration. The tool as used by this hospice was not highly discriminating between the 30% to 40% scores or the 50% to 70% scores.

CONCLUSION: The PPS scores are associated with patient length of survival in a hospice program and can be used in evaluating hospice appropriateness.

Journal of Palliative Medicine (2005) Volume: 8, Issue: 3, Pages: 492-502

“Current literature suggests clinicians are not accurate in prognostication when estimating survival times of palliative care patients. There are reported studies in which the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) is used as a prognostic tool to predict survival of these patients. Yet, their findings are different in terms of the presence of distinct PPS survival profiles and significant covariates.

This study investigates the use of PPS as a prognostication tool for estimating survival times of patients with life-limiting illness in a palliative care unit. These findings are compared to those from earlier studies in terms of PPS survival profiles and covariates.

RESULTS: Study findings revealed that admission PPS score was a strong predictor of survival in patients already identified as palliative, along with gender and age, but diagnosis was not significantly related to survival. We also found that scores of PPS 10% through PPS 50% led to distinct survival curves, and male patients had consistently lower survival rates than females regardless of PPS score.

CONCLUSION: Our findings differ somewhat from earlier studies that suggested the presence of three distinct PPS survival profiles or bands, with diagnosis and non-cancer as significant covariates. Such differences are likely attributed to the size and characteristics of the patient populations involved and further analysis with larger patient samples may help clarify PPS use in prognosis.”

Journal of Palliative Medicine (2006) Volume: 9, Issue: 5, Pages: 1066-1075

“The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) was first introduced in 1996 as a new tool for measurement of performance status in palliative care. PPS has been used in many countries and has been translated into other languages.

Results: The intra-class correlation coefficients for absolute agreement were 0.959 and 0.964 for Group 1, at Time-1 and Time-2; 0.951 and 0.931 for Group 2, at Time-1 and Time-2 respectively. Results showed that the participants were consistent in their scoring over the two times, with a mean Cohen's kappa of 0.67 for Group 1 and 0.71 for Group 2. In the validity study, all experts agreed that PPS is a valuable clinical assessment tool in palliative care. Many of them have already incorporated PPS as part of their practice standard.

Conclusion: The results of the reliability study demonstrated that PPS is a reliable tool. The validity study found that most experts did not feel a need to further modify PPS and, only two experts requested that some performance status measures be defined more clearly. Areas of PPS use include prognostication, disease monitoring, care planning, hospital resource allocation, clinical teaching and research. PPS is also a good communication tool between palliative care workers.”

BMC Palliative Care (2008) Volume: 7, Issue: 2, Publisher: BioMed Central, Pages: 10

|