|

James L. Holly, M.D. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SETMA Plan of Care for Pain Management and Management of other Medications with a High Potential for Habituation Tutorial

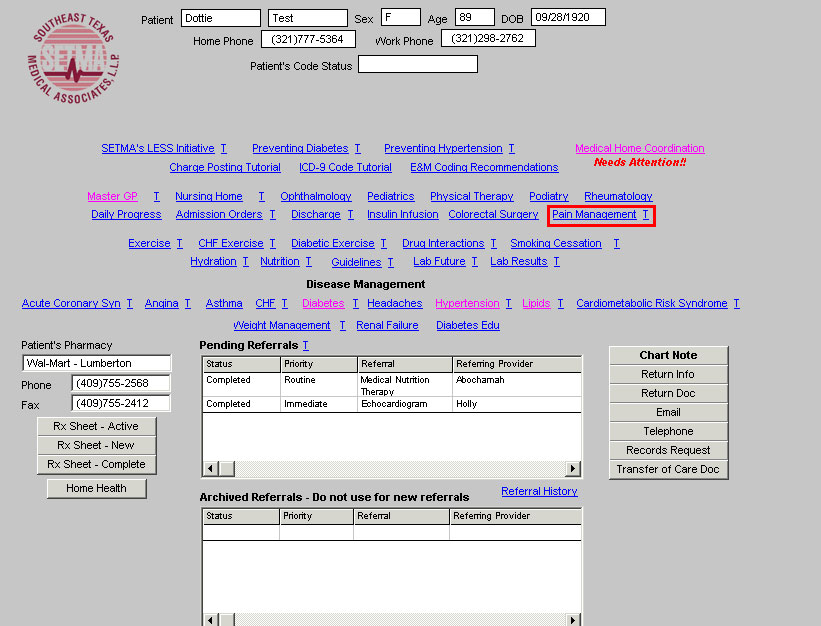

SETMA’s Pain Management template can be accessed by clicking on the Pain Management link on the fourth line of AAA Home. Presently the template consists of one template but will soon be joined by the following materials:

- A review of all medications commonly used for Chronic Pain Management including opioid and non-opioid pain medications, anti-depressants, NSAIDs and anti-convulsant medications.

- Algorithm for the treatment of chronic pain

- Initiation of therapy for chronic pain

- Review of efficacy of treatment for chronic pain

- Additional educational aids for patients and providers on neck and back pain, migraines, fibromyalgia, etc.

When that material is developed and in production, this tutorial will be modified to include it.

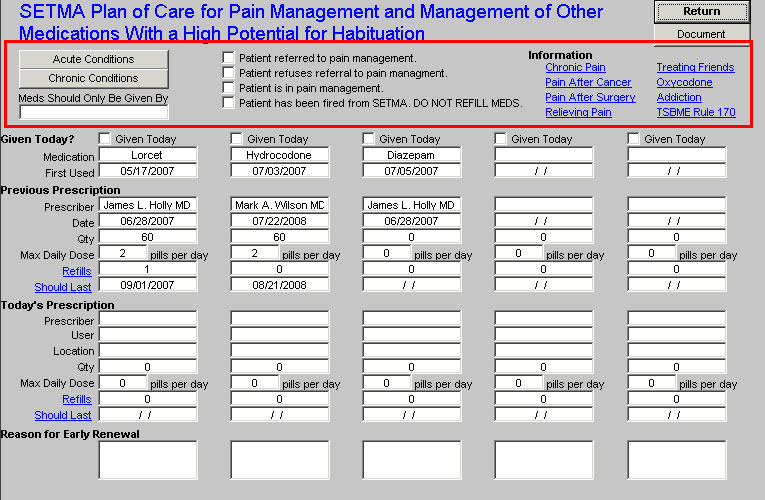

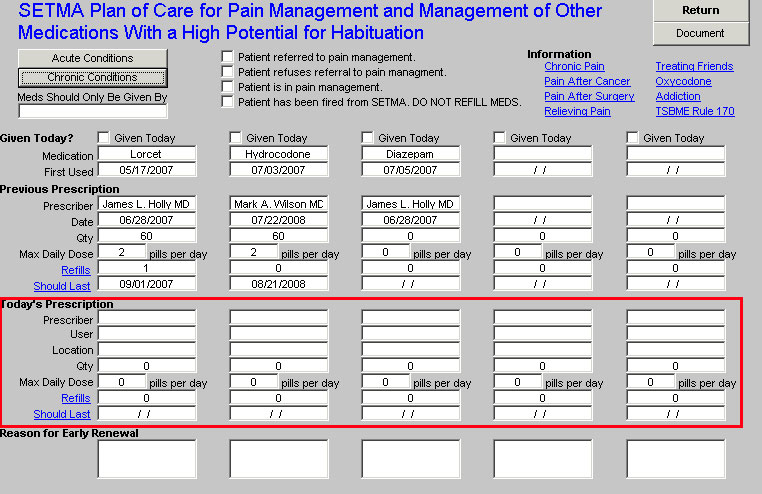

When accessed this template is divided into six sections. The top section contains the following:

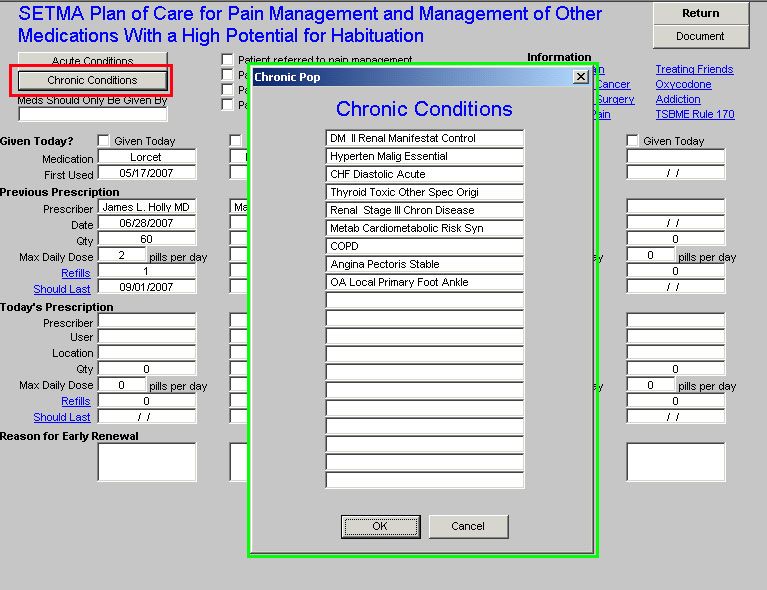

- In the first column there are buttons which lists the:

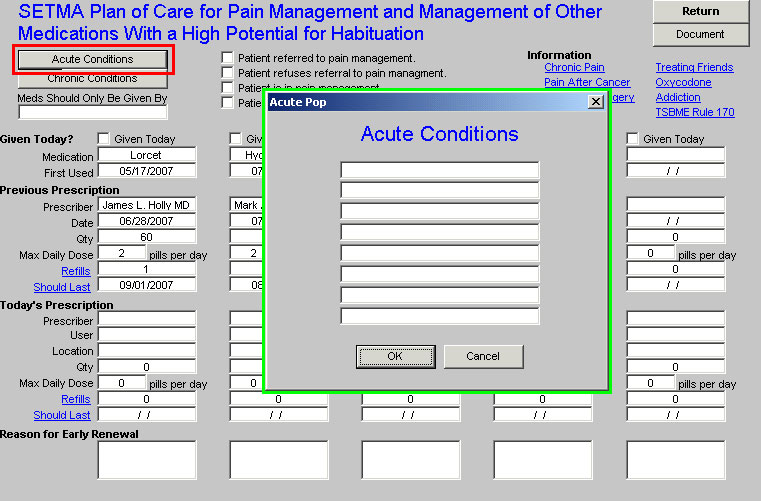

- Acute conditions - if the patient was seen the day the medications of concern were given, then this function will be auto populated from the current encounter. If for some unusual reason, the patient was given these medications without a visit, this section will be empty.

- Chronic conditions - this will enumerate all of the chronic conditions for which the patient is being followed.

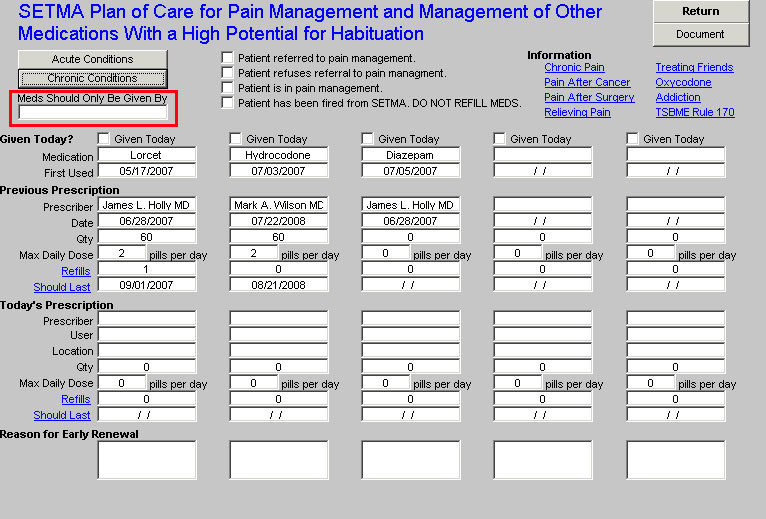

- Meds Should Only Be Given By: A space for documenting that an agreement has been reached with the patient and practice that only the designated and noted provider will refill medications.

It is very important that either the acute or the chronic, or both the acute and chronic diagnoses clearly identify the reasons for the treatment of chronic pain.

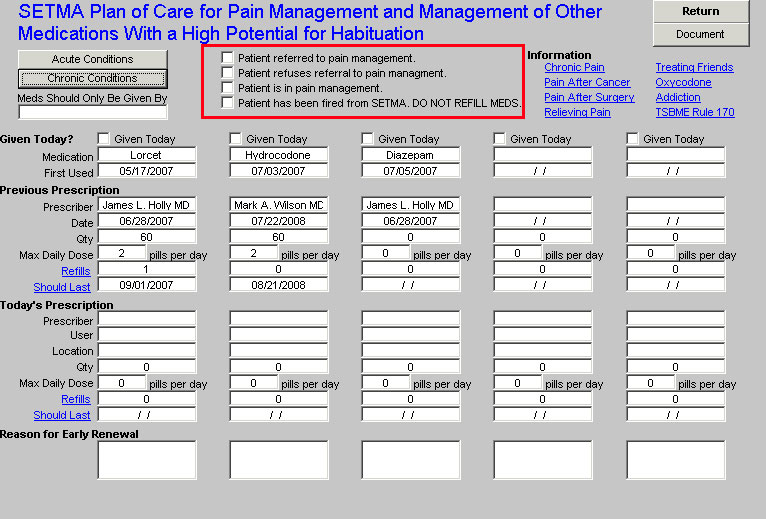

- In the second column there are four options with check boxes which give clarifying information for chronic pain management. Each of these is a reason why the patient’s pain medications should not be refilled by SETMA:

- Patient referred to pain management

- Patient refuses referral to pain management

- Patient is in pain management

- Patient has been fired from SETMA: DO NOT REFILL MEDS.

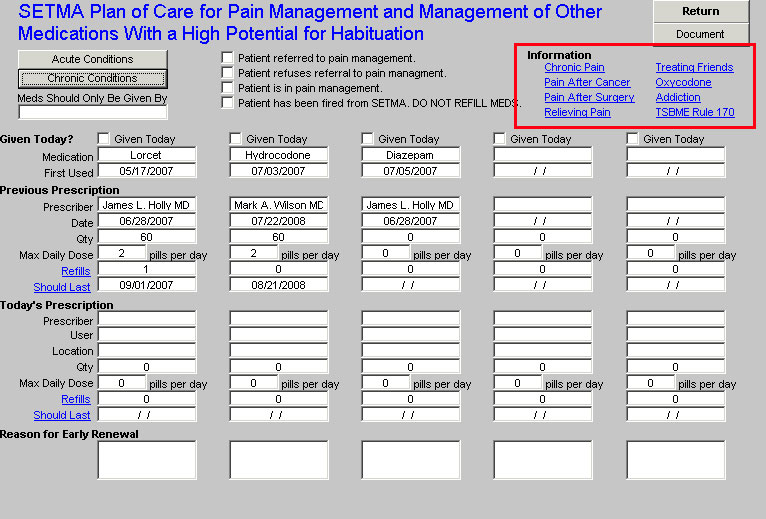

- In the third column there are a number of articles which provide information for patients and for providers on various issues related to pain management. As mentioned above this will soon be expanded.

- TSBME Rule 170 - the text of the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners Rule 170 which is entitled, "Authority of Physician to Prescribe for the Treatment of Pain, Chapter 170.1-170.3."

- Chronic Pain

- Pain After Cancer

- Pain After Surgery

- Relieving Pain

- Treating Friends - this is an extract from the Texas State Board of Medical Examiner’s publication entitled, "The Devil is in the Details." It is very important that all SETMA providers be aware of this publication and of the requirements of the Board for the treatment of friends, family and colleagues.

- Oxycodone

- Addiction

- Others -- will be added soon including a series on neck and back pain, migraines, fibromyalgia, etc.

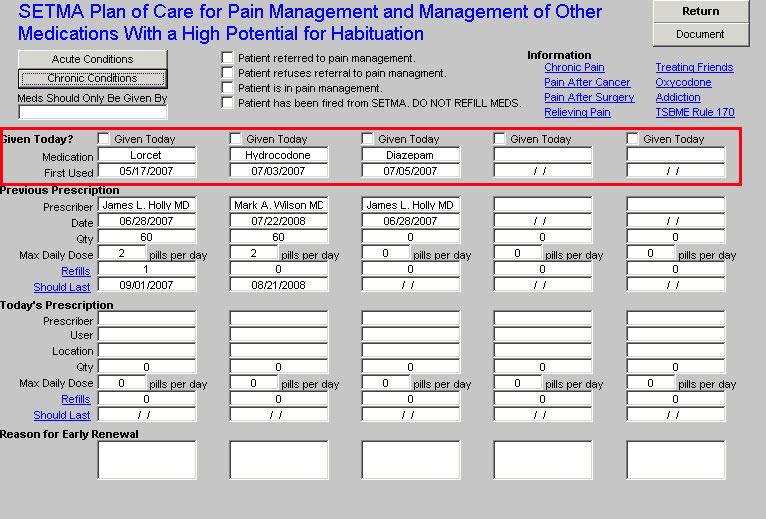

The next section contains five columns where five different pain medications and/or medications with a significant potential for habituation can be listed document with the following specifics:

- Given today? -- this is a check box where it can be documented that a medication was prescribed today.

- Medication - the medication which is being prescribed. The following is a list of the medications which are currently on the pick list for documentation. Others will be added as they are identified by the Therapeutics Committee.

- First Issued - this is a required field which will document how long the patient has been receiving this medication. It does not necessarily follow that the patient has been on this medication continuously from the date that it was first prescribed

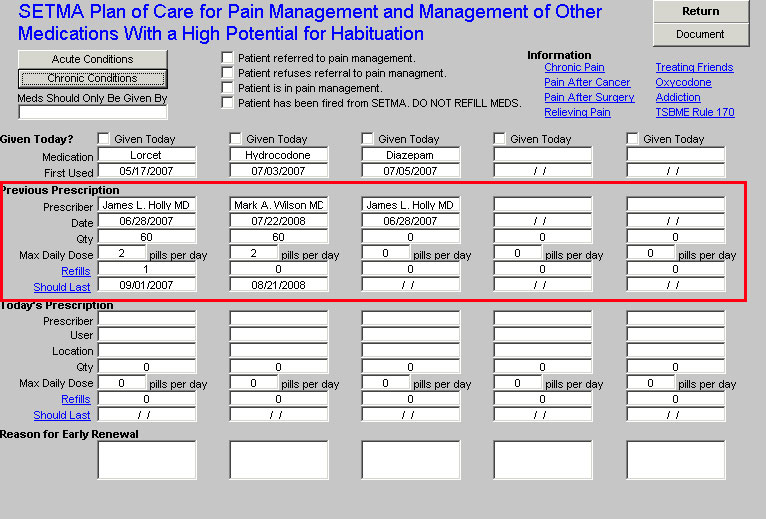

- Previous Prescription

NOTE: This section will be pre-filled from the "Today's Prescription" section from prior visits

- Prescriber - identifies the provider who authorized and/or issued the prescription

- Date - the date of the prescription was given

- Quantity - the number of pills, tablets, suppositories or capsules which were authorized

- Max Daily Dose - the number of the maximum daily dose which is prescribed, i.e., if the prescription is 1-2 po TID prn pain, the maximum daily dose would be 6; if the prescription is 1 po qid prn pain, the maximum daily dose would be 4.

- Refills - the number of refills authorized on the prescription

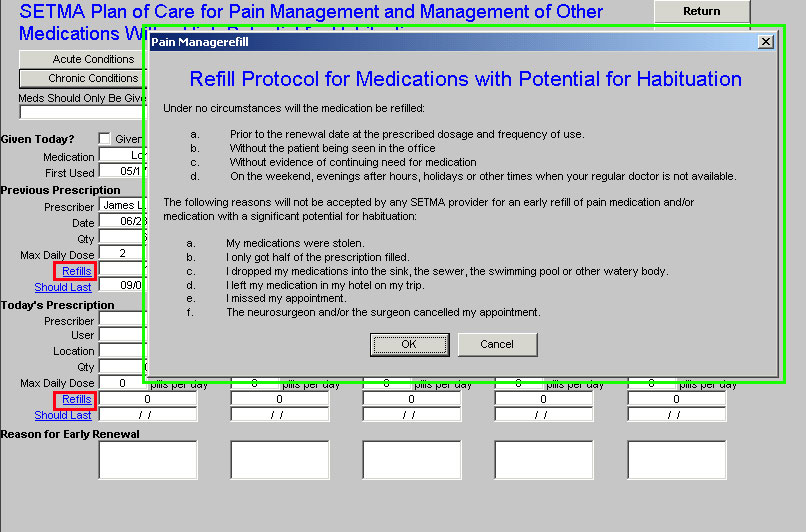

This represents SETMA's refill policy. This policy will print on the pain management

document that will be given to the patient at the end of the visit. This policy states:

Under no circumstances will the medication be refilled:

- Prior to the renewal date at the prescribed dosage and frequency of use.

- Without the patient being seen in the office

- Without evidence of continuing need for medication

- On the weekend, evenings after hours, holidays or other times when your regular doctor is not available.

The following reasons will not be accepted by any SETMA provider for an early refill of pain medication and/or medication with a significant potential for habituation:

- My medications were stolen.

- I only got half of the prescription filled.

- I dropped my medications into the sink, the sewer, the swimming pool or other watery body.

- I left my medication in my hotel on my trip.

- I missed my appointment.

- The neurosurgeon and/or the surgeon cancelled my appointment.

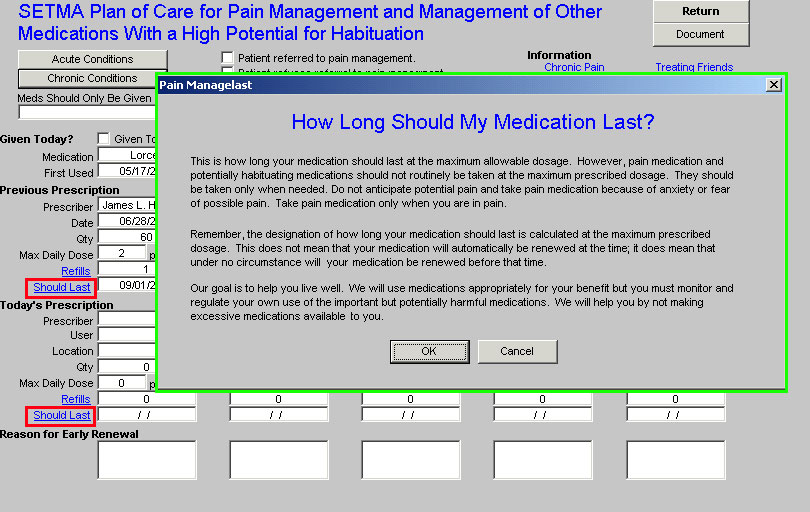

- Should Last - the date will automatically appear here which is a calculation of the number of pills given including refills and the maximum daily dose. This date will be the minimum time for a refill but does not indicate that the prescription should be refilled on this date. See explanation in number five below

It should be explained to the patient that medication may not even be refilled after the

"Should Last" date has expired. The following will print with the patient's pain management

document:

This is how long your medication should last at the maximum allowable dosage. However, pain medication and potentially habituating medications should not routinely be taken at the maximum prescribed dosage. They should be taken only when needed. Do not anticipate potential pain and take pain medication because of anxiety or fear of possible pain. Take pain medication only when you are in pain.

Remember, the designation of how long your medication should last is calculated at the maximum prescribed dosage. This does not mean that your medication will automatically be renewed at that time; it does mean that under no circumstance will your medication be renewed before that time.

Our goal is to help you live well. We will use medications appropriately for your benefit but you must monitor and regulate your own use of the important but potentially harmful medications. We will help you by not making excessive medications available to you.

NOTE: This section will populate the "Previous Prescription" section automatically on next visit

- Prescriber - see above

- Location - this indicates whether the prescription was given by telephone request or at a visit.

- Quantity - see above

- Max. Daily Dose - see above

- Refills - see above

- Should Last - see above

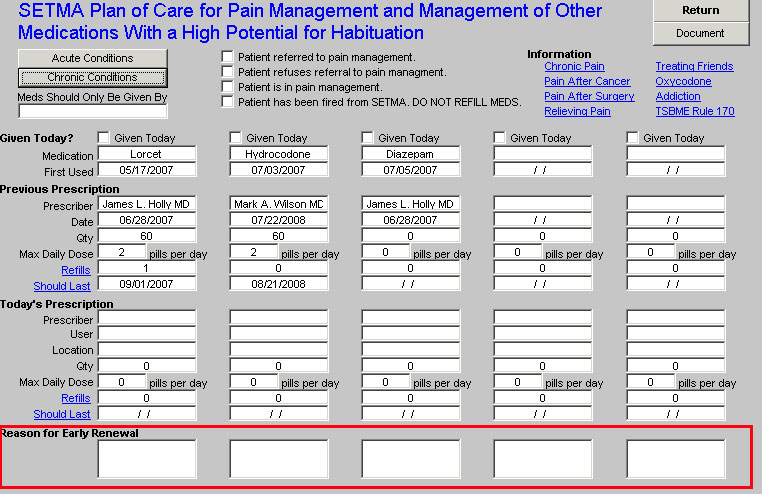

- Reason for Early Renewal - if a prescription is given before the absolute minimum date for a refill, an explanation for the reason should be documented here.

- Clarification of the "Should Last" Concept - on the template, the following will appear:

This is how long your medication should last at the maximum allowable dosage. However, pain medication and potentially habituating medications should not routinely be taken at the maximum prescribed dosage. They should be taken only when needed. Do not anticipate potential pain and take pain medication because of anxiety or fear of possible pain. Take pain medication only when you are in pain.

Remember, the designation of how long your medication should last is calculated at the maximum prescribed dosage. This does not mean that your medication will automatically be renewed at the time; it does mean that under no circumstance will your medication be renewed before that time.

Our goal is to help you live well. We will use medications appropriately for your benefit but you must monitor and regulate your own use of the important but potentially harmful medications. We will help you by not making excessive medications available to you.

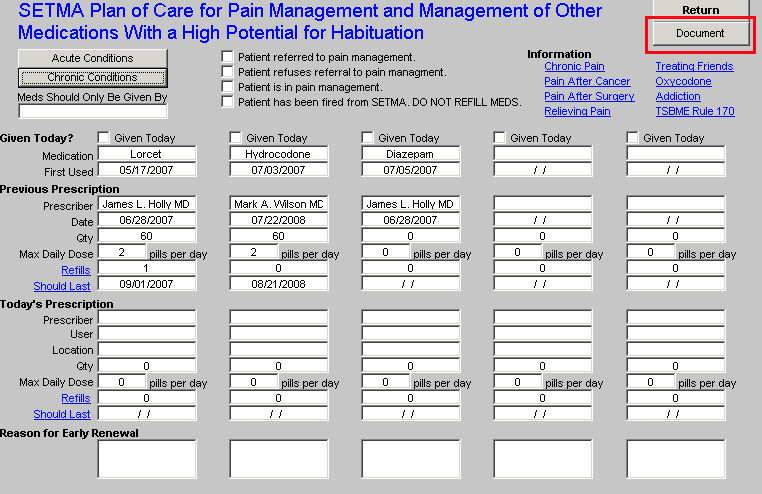

- Document - once the template has been completed, the document button at the top right should be clicked. This will auto print a document which will give the patient all of the information listed above as well as the following:

Goals of Pain Medications

When considering use of pain medications, four goals should be kept in mind.

Reduction in pain intensity. This goal is obvious. However, it is not always realistic to expect that medications will totally eliminate your pain. A more realistic goal may be to relieve pain to a level that can be more easily tolerated and that enables you to continue functioning.

Improve ability to function. This goal is very important, but is sometimes overlooked. Often patients receive significant pain relief from medications, however, these same medications also greatly interfered with the person's ability to function.

Minimize adverse side effects. Keep in mind that there is no such thing as a totally safe pain medication. All have the potential for negative side effects. The goal is to find medications which maximize the benefits while keeping the side effects to a minimum.

Prevent addiction. Most people don't like the idea of getting addicted to their pain medications. However, many people fail to understand what addiction really means and are unaware of the fact that the majority of people who use pain medications as prescribed do not get addicted.

Pain medications are not therapeutic but only suppress symptoms until a diagnosis and treatment plan has been established. The long term, chronic use of pain medications and potentially habituating medications should be avoided when at all possible.

SETMAs desire is to help you recover from any condition which produces chronic pain, to help you live with any untreatable or incurable condition which causes pain and to help you control your use of pain medications in order to protect your health and improve your state of well being.

We will be happy to discuss our pain management policy with you. Our motto, "Healthcare where your health is the only care," is no where truer than when you are in pain.

We will be pleased to refer you to a pain management specialist if you desire.

I have explained to Patient Name that these medications have a significant potential for habituation but are useful when used only as prescribed.

Under no circumstances will the medication be refilled:

- Prior to the renewal date at the prescribed dosage and frequency of use.

- Without the patient being seen in the office

- Without evidence of continuing need for medication

- On the weekend, evenings after hours, holidays or other times when your regular doctor is not available.

The following reasons will not be accepted by any SETMA provider for an early refill of pain medication and/or medication with a significant potential for habituation:

- My medications were stolen.

- I only got half of the prescription filled.

- I dropped my medications into the sink, the sewer, the swimming pool or other watery body.

- I left my medication in my hotel on my trip.

- I missed my appointment.

- The neurosurgeon and/or the surgeon cancelled my appointment.

The following article will also auto print on this document:

Relieving Pain

The lucky among us have only an occasional headache. For others, pain is a constant, though unwelcome, companion. Relieving pain is sometimes simple, sometimes impossible. It depends on the source of the pain and it may also depend on the person.

Everyday Aches and Pains

There are three main nonprescription choices for pain relief:

- Aspirin

- acetaminophen (Datril, Tylenol and others), and

- ibuprofen (Motrin IB, Advil, Nuprin, and others)

All three block the production of chemicals called prostaglandins, which the body usually releases when cells are injured. Prostaglandins are believed to play an important role in the pain, heat, redness, and swelling that occur following tissue damage.

So what's the best choice for your headache, pulled muscle, or menstrual cramps?

When it comes to mild, nonspecific pain, headaches, or menstrual discomfort, "all three [nonprescription pain relievers] are quite useful," says Patricia Love, M.D., a rheumatologist with FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. "There are probably persons who are not able to detect a difference in the effectiveness of the OTC products." It has been suggested, Love says, that aspirin or ibuprofen may be more effective than acetaminophen for pain caused by inflammation or mild menstrual discomfort because they have more prostaglandin-blocking effects. "Our best advice at present is that, for mild pain, individuals may use what works best and is safe for them," says Love.

In other words, what doesn't cause them problems. Because prostaglandins play a role in protecting the stomach lining from being attacked by the acid of digestive fluid, aspirin, ibuprofen, and, apparently to a lesser extent, according to Love, acetaminophen may cause stomach irritation, ulcers or bleeding. "If you have a history of stomach disorders, first talk to your doctor [before taking a nonprescription pain reliever]," says Love.

For some people who take aspirin, stomach irritation may be decreased by taking either enteric-coated aspirin, buffered aspirin, or other modified aspirin derivatives such as choline salicylate or magnesium salicylate. Buffered aspirin contains an ingredient that neutralizes some of the digestive system's acid and, therefore, may produce less irritation than plain aspirin.

Coated aspirin dissolves mainly in the intestine. (Uncoated aspirin dissolves in the stomach.) In theory, that difference may mean less stomach irritation says Love. But, she adds, it still depends on an individual's metabolism. For example, some people can't digest the coating, so while they don't get any stomach irritation, they don't get any benefit either. The aspirin passes out of the body undigested and unabsorbed.

People who can't take aspirin because of allergic reactions (e.g., rash, asthma, anaphylaxis) generally can't take ibuprofen either. For them, acetaminophen may be the only nonprescription choice. "Persons with medication allergies should discuss the use of any nonprescription medication with their doctor," Love says. She adds that all three drugs have the potential to cause liver damage, although liver toxicity is much less common than gastric ulcers or bleeding. FDA is reviewing recent studies that suggest an association between use of all three nonprescription pain relievers and kidney disease. But the agency says that not enough is known yet about these possible associations to make any changes in current recommendations for use for healthy individuals.

"I think one of the important safety issues in choosing a medication is it's not just whether or not you have minor pain, but what is your medical history on top of the minor pain," says Love. "People who have specific disorders--kidney disease, heart disease, bleeding problems, liver disorders, medication allergies--should talk to their physicians."

Acute Pain from Injury or Surgery

When the pain becomes too much to bear, or is the result of a serious injury or surgery, relief requires stronger medicine and a doctor's prescription. One class of frequently prescribed pain relievers is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, often abbreviated NSAIDs. (The three nonprescription pain relievers are also NSAIDs, according to Love, although acetaminophen is not commonly referred to by that term.)

Prescription NSAIDs are given at higher doses than the nonprescription types, but the mechanism for pain relief is the same--blocking the production of prostaglandins

Opiate drugs are another class of pain-relieving prescription drugs. Commonly prescribed opiates include morphine, codeine, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and meperidine (Demerol). (In some states, some forms of codeine are sold without a prescription in limited amounts.) Most of these drugs are derived from opium, the juice of the poppy flower.

Opiate drugs work by altering the transmission of pain messages in the brain and spinal cord, blocking pain messages or altering their character. The pain-blocking action of the opiates can be enhanced by taking aspirin, ibuprofen or acetaminophen at the same time as the opiate. This hits pain with a "double-whammy." The NSAIDS block the pain at the site of injury, while the opiates suppress in the brain any remaining pain.

Unfortunately, the effect of opiates on the brain isn't limited to pain control. Opiates can cause drowsiness, nausea, constipation, and unpleasant mood changes in some people. However, sometimes simply trying a different opiate may be all that's needed to reduce these side effects.

Tolerance and Addiction

Because doctors are afraid patients may become dependent on opiate drugs, they sometimes hold back on the amount or number of doses, even if this means the patient doesn't get sufficient pain relief. Ronald Dubner, D.D.S., chief of the Neurobiology and Anesthesiology Branch of the National Institute of Dental Research, says those fears are unfounded. But, he explains, "One needs to be very clear about making the distinction between tolerance and addiction."

Tolerance occurs when the body no longer responds as well to the opiate's pain-relieving properties at the current dose. For example, some cancer patients with severe pain may need increasing amounts of morphine to maintain the same level of pain relief. Addiction, on the other hand, is an overwhelming compulsion to continue use of the drug even when pain relief is no longer needed. While some of the addiction is physical, it is mainly considered a psychological dependence that has a detrimental effect not only on the individual, but also on society, because the addicted individual may have to obtain the drug illegally.

Addiction is "really a red herring in the field of pain control," says Dubner. The fear that giving patients opiates will turn them into addicts craving the drugs long after the pain has ended is unfounded, says Dubner. "People who are truly seeking help for their pain and who are in good hands do not have addiction problems," he explains.

In any case, Dubner says, it is very rare for a patient to reach a point where no amount of an opiate will relieve pain and that should never be used as a reason for not increasing the drug's dose. Anesthesiologist Francis Balestrieri agrees. "There's no reason to hold back the drug dose for people in acute pain," says Balestrieri, who is the director of the Woodburn Surgery Center at Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va. However, FDA's Curtis Wright, M.D., warns that the pain relief from higher doses of opiates must be weighed against the side effects these drugs can cause. "It's a balancing act," says Wright, who is a medical review officer for the agency's center for drug evaluation and research. "The amount of pain relief must be weighed against the effects of adverse reactions such as agitation, nausea, confusion, and potentially lethal respiratory depression."

Patients in Control

Frequently, however, the doses of narcotics physicians prescribe are too low, not too high, and the time between doses is too long, according to a book by Barry Stimmel, M.D., Pain, Analgesia, and Addiction: The Pharmacologic Treatment of Pain. Stimmel writes that, "Analgesic medications should be prescribed regularly around the clock in the presence of acute pain. The intervals between administration should be sufficiently close together to avoid swings in pain levels. Both laboratory and clinical studies have shown that the presence of anxiety will result in an increased need for narcotics, thus setting up a vicious cycle whereby escalating doses of analgesics are needed, without adequate pain relief being obtained." The use of analgesics provides more benefits to the patient than just relieving pain.

"Evidence from laboratory experiments has begun to accumulate showing that pain can accelerate the growth of tumors and increase mortality after tumor challenge," writes John C. Liebeskind in an editorial in the January 1991 issue of pain. "It appears that the dictum 'pain does not kill,' sometimes invoked to justify ignoring pain complaints, may be dangerously wrong." Dubner agrees. "Pain is not a passive symptom. We consider pain, in many instances, an aggressive disease in itself. Therefore it becomes very, very critical to control pain as rapidly and as completely as possible."

One solution to inadequate doses of pain relievers is patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCA), which is usually used in hospitals for acute pain following surgery. In PCA, the patient is connected to a machine called a PCA pump. When the patient pushes a control button, the machine delivers a dose of narcotic or other pain reliever intravenously. The doses are smaller than what would be given by injection, but because the drug goes directly into the bloodstream, relief can occur within seconds. A patient receiving traditional administration with an injection in the muscle or under the skin, may have to wait anywhere from 5 to 30 minutes for pain relief. Although the pain relief with PCA's small doses may only last for 10 to 15 minutes, the patient can get another dose the second pain begins to return. Injections, on the other hand, may last up to two hours, but since the usual dosage schedule is three to four hours, the pain returns long before the nurse does.

"PCA matches the patients' relief to their pain," says Balestrieri. "It also relieves patients of the worry over their pain relief in the majority of cases." It also helps patients deal with the side effects opiates can cause, says FDA's Wright."A substantial portion of patients don't want complete pain relief," says Wright. "They want as much pain relief as they can get without bad side effects."

Wright says that when the first studies were done on the effectiveness of PCA, "we thought that the pain scores [the patients gave] would be zero." (Patients generally rated pain on a four-point scale with four being the greatest amount of pain and zero, no pain.) "What we found was that patients didn't titrate down to zero, but instead brought the pain down to one or two," he says.

The undesirable side effects of narcotics can be avoided completely with another form of continuous administration--epidural therapy. Epidurals, which inject the narcotics into the membrane surrounding the spinal cord, have been used for many years to block the pain of labor. Now this is being adapted to control pain after some major surgery, especially abdominal. Drugs injected into the epidural space don't travel to the brain like other types of injections, explains Sherry Fisher, R.N., pain management coordinator at Fairfax Hospital. Therefore, complications such as nausea and respiratory depression don't occur.

With epidurals "patients can talk to me, take deep breaths, cough, and even be up and walking around, sometimes 24 hours after surgery," says Fisher. Normally, after the type of major surgery that requires the kind of pain control epidural therapy provides, "the patient would still be on a ventilator after 24 hours," she says.

However, epidurals aren't effective for every type of pain. Besides pain from abdominal surgeries, epidurals are best used for pain following major chest and urologic surgery, according to Fisher. No matter what the form of administration, "I don't think people should be exposed

Chronic Pain

Unfortunately, "when it comes to chronic pain, there are situations where pain cannot be controlled as well with the approaches that are available to us today," says Dubner. Opiate drugs are usually avoided in chronic pain management because of the potential for tolerance.

Some types of chronic pain that are difficult to control include:

- pain from nerve damage caused by diabetes or shingles

- lower back pain that continues long after the initial injury has healed

- arthritis

- migraine and other chronic headaches.

There is some hope though. Tricyclic antidepressants, especially amitriptyline, have been found to relieve pain in patients with nerve damage. These drugs aid the body's own defenses by trapping serotonin, a pain-blocking chemical, at its point of production in the nerve endings in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. An excess of serotonin builds up and suppresses pain signals longer than usual.

Although FDA has not approved tricyclic antidepressants for pain control, these drugs are gaining wide acceptance for this purpose. (The practice of medicine may include the prescribing of approved drugs for unapproved uses supported by research and not otherwise contraindicated.)

Treatment of chronic and migraine headache pain may include two drugs approved for heart problems--calcium channel blockers and beta blockers. Treatment for mild arthritis pain, on the other hand, often begins with aspirin. If the patient can't tolerate aspirin, ibuprofen is a reasonable substitute, says Love. She warns, however, that even though people can buy aspirin and ibuprofen without a prescription, the doses required to treat arthritis pain are too high to be taken without a physician's care. "The treatment of chronic arthritis, regardless of severity, requires an adequate diagnosis and possible use of many different types of medications, physical therapy, or surgery," says Love.

TENS

Another potential source of relief for chronic pain is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Through the use of the TENS device--a battery-powered generator that could be mistaken for a Walkman portable radio or a beeper--electrical impulses are transmitted to the site of pain through electrodes placed on the skin.With the most common course of treatment, the physician or physical therapist sets the TENS device to deliver 80 to 100 impulses a second for 45 minutes, three times a day.

But there are a wide variety of parameter ranges, and what works for one person may have no effect on another. Determining the most effective settings "is a real art," says Stephen M. Hinckley, a physiologist with FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Pain can be very subjective, explains Hinckley. Two people whose pain is caused by the same problem may need very different settings to achieve relief. If a patient doesn't require hospital care, the patient can use the TENS device, preset to the proper level, at home. The device does not interfere with most normal activities.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in June 1990 questioned the effectiveness of TENS. The study concluded "that for patients with chronic low back pain, treatment with TENS is no more effective than treatment with a placebo, and TENS adds no apparent benefit to that of exercise alone."

But, because a number of previous studies support the use of TENS, FDA still considers TENS to be effective for pain relief for some people. Although it isn't clear why TENS works, there are two plausible theories, according to the Harvard Medical School Health Letter. The first holds that nerves can easily carry only one message at a time. The electrical pulses from TENS overload the nerves, and the pain message shuts down. A second theory hypothesizes that the electrical pulses stimulate the body to release its own painkilling molecules, called endorphins, into the fluid bathing the spinal cord.

Pain researchers are studying how to stimulate production of the brain's own opiates, such as endorphins, enkephalins and dynorphins, since they may act as natural painkillers, according to NIH's Dubner. "There are clear indications that stimulation in certain parts of the brain can be helpful in some patients," he says.

Focus on Life

Sometimes, though, none of these therapies will completely relieve the pain for chronic sufferers. They don't have to give up hope, though. For many in chronic pain, behavior modification techniques such as biofeedback, meditation and relaxation training may offer some relief. These treatment approaches are designed to alter a patient's reactions and behavior in response to pain.

"They learn that they can deal with their pain effectively if they focus on improving their quality of life instead of focusing on their pain," says Dubner. Seymour Rubin, 67, who has suffered with chronic back pain for 40 years, agrees. "If I focus on the pain, it just gets worse," he says. Instead, Rubin keeps busy with walking, reading, and running errands with his wife. "Singing helps, talking helps," adds Rubin. "And I've just learned to accept the fact that I have pain."

How You Know That You Stubbed Your Toe

- Nociceptors are specialized nerve endings in the skin and other peripheral tissues that respond exclusively to tissue-damaging stimuli. Prostaglandins sensitize these nerve endings, and the pain message starts on its way to the brain. Aspirin and ibuprofen and, to a lesser extent, acetaminophen can block prostaglandin production at this point.

- Pain travels along special nerve fibers to the part of the spinal cord called the dorsal horn.

- Tricyclic antidepressants work here by enhancing the effects of the body's own natural painkillers.

- From the dorsal horn, the pain ascends to the thalamus and then to the cerebral cortex. Opiates cause the brain to suppress pain messages before they leave the dorsal horn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|