|

July 23, 2013

Joseph Bujak comment: “These represent the intended approach of a professional. Someone for whom being a physician is their self-identity. It is their life's work and not a job. This attitude is being extinguished as being a doctor becomes a job, a means to an end, only a part of one’s self-identity. Don't think that this is an either/or, but a both/and. Perhaps hospitalists can bridge the gap since they don't have to "run off' to the office after morning rounds. But the nature of relationship seems to me to be in conflict with the concept of shift work. Otherwise the moving parts need to be interchangeable. That concept too stands to challenge professionalism. What do you think Larry?” To which Dr. Holly sent the following response.

Many of the issues which you raised in your comments and in your questions are addressed in the section under Letters’ entitled Medical Home News July 1, 2013 Subscription Medicine. This is a dialogue with the author of an article which appeared July 1, 2013 in Medical Home News. The author advocates for patients “buying” a relationship with a healthcare providers with a monthly “subscription payment” not unlike concierge medicine. That dialogue can be found at http://jameslhollymd.com/letters/ just beneath this discussion of HCAHPS. My first response to the article is found at http://jameslhollymd.com/Letters/Medical-Home-News-July-2013-Response-to-Alex-Tolberts-Top-Three-Obstacles-to-Better-Primary-Care. My response contrasts the difference between Patient-Centered Medical Home and Concierge (Subscription) Medicine. In that article the following links to other articles about “Concierge Medicine” and “Entrepreneurism in healthcare” appear:

Your comment of “being a doctor becom(ing) a job” is right on point as it leads to “shift work.” Rather than a healthcare provider, whether physician or nurse practitioner, assuming continuous responsibility for the healthcare of a population of patients, that responsibility is limited to a period of time, i.e., a shift of work. Continuity of Care then becomes a function of a “handoff” from one provider to another - one completing a shift and another starting a shift. Between shifts there is no communication or assess to the provider who has “signed off.” The Transition of Care from shift to shift is significantly different from the Transition of Care from one venue to another.

In the Patient-Centered Medical Home model high value is placed on a personal, continuous relationship between a patient and a provider. And, while that is a very good thing, I have and continue to argue that the ideal continuity to care is driven by data contained in a robust electronic medical records which is available at every point of care regardless of which provider is meeting the needs of the patient. Quickly, one might say, but isn’t that the same thing as shift work? Isn’t a clinic setting, where the patient may see a different provider fraught with the same problems as providers who work a shift? Just as quickly, I would say, it can be IF members of the healthcare clinic or team do not share responsibility for the patient’s or the population of patients welfare. The difference is that the team members are equally responsibility for the well being of the patients they commonly see. They do not turn over responsibility with another person with no expectation of “follow-up” to see how the patient is doing and/or with the expectation of never seeing that patient again.

It is hear where communication becomes very important. Each member of the team remains in the communication loop in order to continually interact with all providers caring for a patient, adding their perception, expertise and diagnostic and therapeutic acumen to the treatment of the patient. In a similar time, one patient saw one provide. When that provider was not available, the patient might get emergency care but not continuing care in the context of a defined plan of care and treatment plan. Personal relationships are valuable but that personal relationship can be with a team where the patient has confidence that the team, acting like a surrogate for an individual provider, gives their full attention and their continuous attention to the patient’s health and welfare.

Hospitalist

In this context a hospitalist can act like a shift worker or like a team member. The difference is critical. When the hospitalist is a shift worker, he/she is available for a prescribed period of time during which patients are evaluated and admitted to the inpatient setting. At the end of the shift another person assumes that responsibility. The hospitalist may or may not be a part of the community, i.e., they may live far away and may simply travel to their “work station” during their shift and then leave. Several years ago, a “hospitalist group” “won” the hospitalist contract for uninsured and unassigned patients at one of our local hospitals. I have just reread my communication with them and the summary of multiple meetings with them. As these were itinerant physicians who were not a part of our community, transitions of care from the inpatient to the ambulatory setting were critical. As it turned out, the group, which works in many communities, had no transition plan and had not plans to develop one. It will not be surprising that in less than one year that group lost their contract and left the community.

Hospitalists which are part of a team, either formally or informally, are ideal. They communication with the patients primary care provider. The records of their care are documented in the same electronic patient record as the ambulatory care delivered by the primary care provider. There is daily communication between the two. Rather than what is called “huddles” where providers physically meet, SETMA has multiple communications daily in secure electronic formats in what we call “electronic huddles.” In this case the patient is getting the benefit of all those who are continuously involved in their care.

Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan - formally called the Discharge Summary

The Transition of Care document is no longer the administrative “discharge summary,” but it is the Hospital Care Summary and the Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan. In 2010, Southeast Texas Medical Associates, LLP (SETMA, www.jameslhollymd.com) realized that the name, “hospital discharge summary,” had lost any significance as a “transition of care” document, therefore, we changed the name to,” Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan.” Over the last three years, SETMA has discharged over 16,000 patients from the hospital. 98.7% of the time, the patient, hospital and care-giver received this document at the time the patient left the hospital. This “Hospital Care Summary” allows for the responsibility for care to be transitioned to the patient or to the care giver, as it is “passed off” at discharge. Containing a reconciled medical list, follow-up appointments, risk of readmission assessment, diagnoses and a plan of care, the “Summary” functions as a “baton.”

But, hospital-to-outpatient is only one of the transitions in patient care as a result of which SETMA prepares several “batons” in the course of every patient’s care, all with the same purpose.

The “baton” illustrates:

- That the healthcare-team relationship, which exists between the patient and the healthcare provider, is key to the success of the outcome of quality healthcare.

- That the plan of care and treatment plan, the “baton,” is the engine through which the knowledge and power of the healthcare team is transmitted and sustained.

- That the means of transfer of the “baton” which has been developed by the healthcare team is a coordinated effort between the provider and the patient.

- That typically the healthcare provider knows and understands the patient’s healthcare plan of care and the treatment plan, but that without its transfer to the patient, the provider’s knowledge is useless to the patient.

- That the imperative for the plan - the “baton” - is that it be transferred from the provider to the patient, if change in the life of the patient is going to make a difference in the patient’s health.

- That this transfer requires that the patient “grasps” the “baton,” i.e., that the patient accepts, receives, understands and comprehends the plan, and that the patient is equipped and empowered to carry out the plan successfully.

- That the patient knows that of the 8,760 hours in the year, he/she will be responsible for “carrying the baton,” longer and better than any other member of the healthcare team.

The genius and the promise of the Patient-Centered Medical Home are symbolized by the “baton.” Its display continually reminds provider and patient, that to be successful, the patient’s care must be coordinated, which must result in coordinated care. As clinics transform into PC-MHs, coordination begins at all points of “care transitions,” and the work of the healthcare team - patient and provider - is that together they evaluate, define and execute care.

Plan of Care: Reviewing Elements of Plan

The great value of a written plan of care and treatment plan is to provide the patient and the patient's family with a means of reviewing what they learned during a hospital stay, a visit to the clinic or to the emergency department. Without the written plan which has the patient's name on every page and which has the patient's personal laboratory and procedure results, little will be accomplished; as in a very short time, humans forget 90% of what they have heard. And, often what a person remembers of what he/she only received audibly is not recalled accurately. With a written plan of care to review, the probability of real learning taking place is greatly enhanced.

Furthermore, as healthcare providers, we are committed to life-time learning; now we want our patients to become students as well. The more the patient learns, the more they participate effectively in their own care. Having had a dialogue with their healthcare provider and having received a printed copy of their plan of care and treatment plan, the patient is prepared to accept responsibility for their own care 8,760 hours a year.

Example of Feedback Loop

Few things are as new, to healthcare providers as the concept of a "feedback loop." Most physicians were trained to have a monologue with patients: tell them what they have; how it is to be treated; and, what they are to do until their next visit. But a didactic exchange without a dialogue often results in two simultaneous monologues without effective communication.

In 2010, I saw a patient for the first time whose father, mother, sister and two brothers had diabetes. I thought, "Aha, I wonder if she has diabetes?" Upon testing, diabetes was proved. The day following the clinic visit, I called the patient and reviewed the diagnosis, condition and plan of care and treatment plan with the patient, which included medications, further evaluation with ophthalmology, endocrinology, diabetes self-management education and medical nutrition therapy and follow-up visits. The plan of care was evidenced-based, coordinated and communicated.

The patient agreed to all of the plans, but as I hung up the telephone, I thought to myself, "This patient is not buying any of it." Using SETMA's Clinic Follow-up Call template, I scheduled a call from our Care Coordination Department for three days later. The call was made and I received the report: the patient appreciated the visit and the call, but she is not going to do the education, take the medication, or have any of the other evaluations.

Unintentional Neglect of a Patient

For several years, I remembered this patient as an example of excellent patient-centered care, until I realized how ineffective the transition of care had been due to my ignoring the patient’s reason for seeing me. As I thought about this patient, I went back and read her record. Over and over and over, the words rang in my head, “I want to lose weight.” I remembered well that once I had completed the patient’s history and settled on treating her diabetes, I unintentionally ignored the patient’s desires. I was certain that the patient had diabetes; which she did. And, I was determined to give the patient excellent care for diabetes; which I didn’t.

Rather than explaining to the patient why I don’t treat weight loss with Ionamin, thyroid and diuretics, I just ignored her goal. Because I ignored the patient’s goal; the patient ignored my plan. I realized that while I would have labeled the patient “non-compliant” using ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes and SNOMED nomenclature for that diagnoses; the real diagnosis should have been “provider failure to communicate,” “non-patient-centric care,” “failure to activate the patient,” and/or “failure to engage the patient.”

The fault was not the patient’s; the fault was mine. What if I had engaged the patient in a conversation about weight reduction? What if I had discussed with the patient, the reasons why I don’t prescribe Ionamin, thyroid medicine and diuretics for weight reduction? What if I had walked the patient through SETMA’s Adult Weight Management program (see at www.jameslhollymd.com, under EPM Tools/Disease Management Tools/Adult Weight Management Tutorial)? What if I had said, “While we are helping you lose weight; we can also help you control your diabetes?”

The recognition of having made a mistake

Plutarch said, “To make no mistakes is not in the power of man; but from their errors and mistakes the wise and good learn wisdom for the future.” My mistake can be forgiven if I learn from it. And, how will I demonstrate learning? I think I shall never see a patient without asking the question, “What is your goal?” “What do you want to achieve in this visit and in the care you will receive from this clinic?”

That question is partially answered when the patient-encounter-record documents the patient’s “chief complaint.” But to make it more explicit, we added a “comment box” which is labeled: “Patient Goal.” It will be expressed in the patient’s words.” While we want to use structured data fields, this may be one case where structured data fields obscure the issue. As we have more experience with shared-decision making, we will clarify this data field more precisely. But, we will never ignore a patient’s personal goal again. And, if the patient’s goal is something which is inappropriate, or which can’t or shouldn’t be done, we will address that directly and frankly, rather than just by ignoring it.

Transitions of care require a tool such as a “baton,” but it also requires the activation of the patient by engaging them in a process of taking charge of their care, and that requires an effective dialogue with the patient. If the patient does not accept the plan of care and does not agree to make that care their own, the transition of care will fail, no matter how good it is. Shift Hospitalist will not be effective in this transition; Team Hospitalist will see this as the heart and core of their professional responsibility.

Joseph Bujak said, “Otherwise the moving parts need to be interchangeable.”

In this, you borrow a metaphor from the industrial revolution, but it is apt to our dilemma. The nature of the “parts” of a machine is that the industrial revolution preserved the life of a tool by making it possible to replace the “piece” which had worn out. It fit; it worked; it succeeded. That is really the nature of a team. With a shared vision, shared passion and a shared, robust, extensive data base, the team can function equally well when all members are present or when some are missing and/or leave. When each member of the team is collaborating with the other members; when each member of the team is continually engaged and involved with the care of all patients; when each member of the team is committed to excellence, they do become interchangeable without losing their sense of personality and individuality.

Joe, I always enjoy your perspective. I find you comments and questions challenging and provocative. Thank you for your time, your heart, your mind and your commitment.

James (Larry) Holly, M.D.

C.E.O. SETMA

www.jameslhollymd.com

Adjunct Professor

Family & Community Medicine

University of Texas Health Science Center

San Antonio School of Medicine

Clinical Associate Professor

Department of Internal Medicine

School of Medicine

Texas A&M Health Science Center

Addendum

Care Transitions

In SETMA's Model of Care (for a full description see SETMA's presentation to the Office of National Coordinator at the following link: Address to the staff of the Office of the National Coordinator HIT, HHS, March 31, 2011), Care Transitions involves:

- Fulfillment of the Physician Collaborative for Performance Improvement (PCPI) Transitions of Care Quality Metric Set which has fourteen data points and four action items.

- Post Hospital Follow-up Call which is a 12-30 minute call which takes place the day after the patient leaves the hospital which is made by members of SETMA's Care Coordination Department.

- Plan of Care and Treatment Plan, which is symbolized by the "baton."

- Follow-up visit with primary provider in less than seven days of discharge and usually within three.

Over the past fourteen years, SETMA has developed numerous tools which enable us to sustain an effort to impact preventable readmission rates. In June, 2009, the PCPI published a quality metric set on Transitions of Care. Because SETMA had been completing hospital history and physicals and discharge summaries in the EHR, we were prepared to deploy this measurement set. We have been successfully doing so since that time with 6,147patients discharged from the hospital.

Changing the Name of the "Discharge Summary"

In September, 2010, at a National Quality Forum workshop of Care Transitions in Washington, it occurred to us that the name "discharge summary" was outdated and not helpful. The document had become almost an administrative function, often completed weeks after the patient left the hospital. It was not the critical element in the patient's moving from their inpatient or emergency department state to the ambulatory or other setting.

We immediately changed the name of that document to "Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan." This is a long and perhaps awkward name, but it is extremely functional, focusing on the unique elements of Care Transition. From June, 2009 to April, 2011, SETMA has a 99.1% rate of completing this document at the time the patient leaves the hospital. During this time we have discharged 6,147 patients from the hospital.

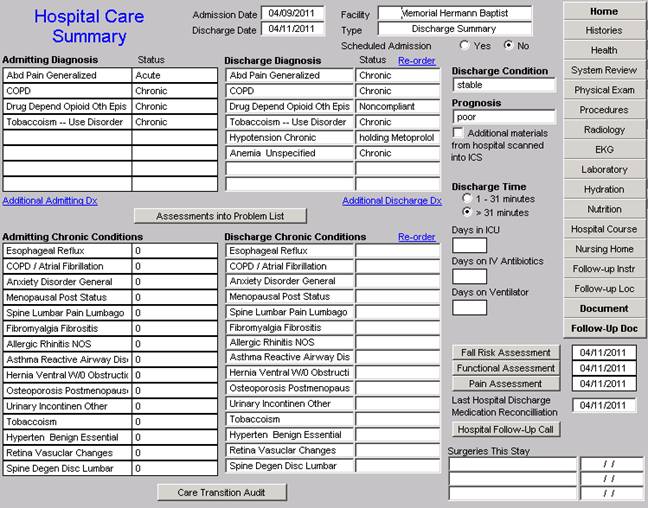

Hospital Care Summary

This is a suite of templates with which the discharge document is created. (For a full description of this see the following on SETMA's website: Electronic Patient Tools; Hospital Care Tools; Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan Tutorial) The following is a screen shot of the Master Discharge Template entitled "Hospital Care Summary". This screen shot is from the record of a real patient whose identify has been removed.

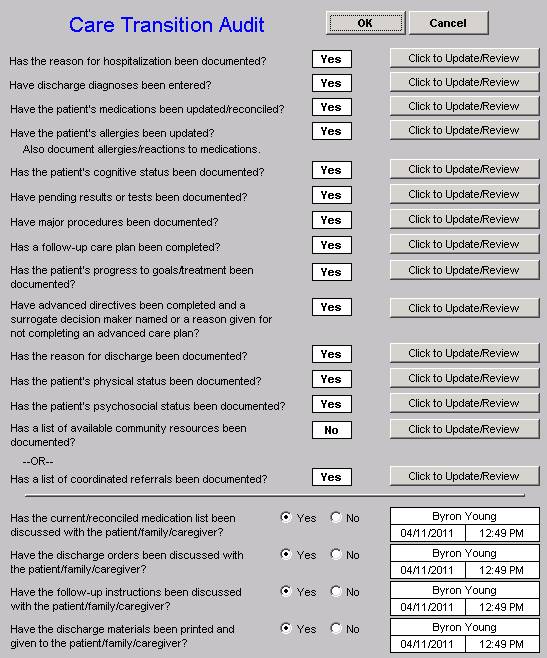

At the bottom of this template you will see a button entitled "Care Transitions Audit." Once the suite of templates associated with the Hospital Care Summary has been completed, the provider depresses this button and the system automatically aggregates the data which has been documented and displays which of the 18-data points have been completed.

The elements in black have been completed; any in red have not.

If an element is incomplete, the provider simply clicks the button entitled "Click to update/Review." The missing information can then be added. This fulfills one of SETMA's principles of EHR design which is "We want to make it easier to do it right than not to do it at all."

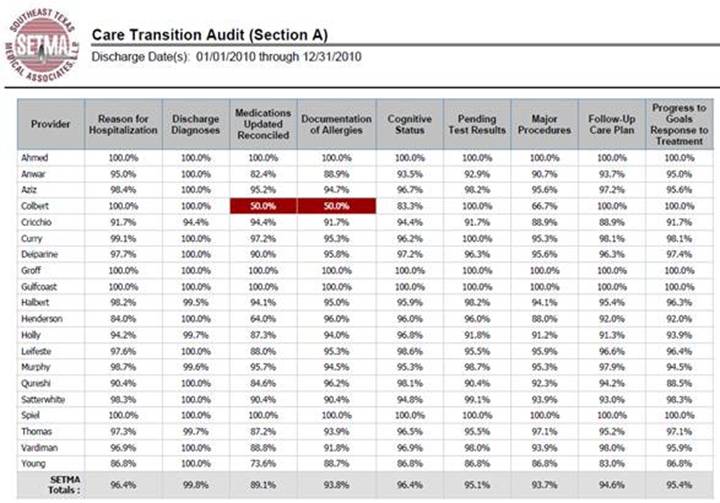

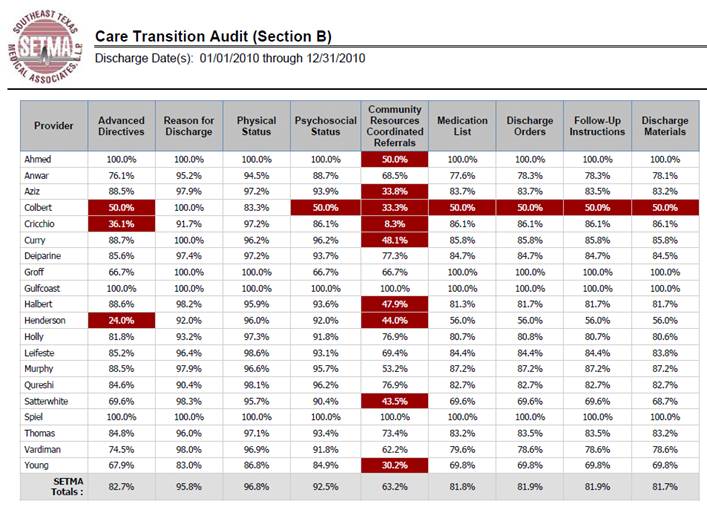

At appropriate intervals, usually quarterly and annually, SETMA audits each provider's performance on these measures and publishes that audit on our website under "Public Reporting," along with over 200 other quality metrics which we track routinely. This reporting is done by provider name. The following is the care transition audit results by provider name for 2010. This presently is posted on our website. The audit is done through SETMA's COGNOS Project which is described in detail on our website under Your Life Your Health by clicking on the icon entitled COGNOS.

Once the Care Transition issues are completed, the Hospital-Care-Summary-and-Post- Hospital-Plan-of-Care-and-Treatment-Plan document is generated and printed. It is given to the patient and to the hospital. The complexity of the Transition of Care is illustrated by this analysis of how many different places this document can be needed. It can go from:

- Inpatient to ambulatory outpatient (family) -- The "baton" in a printed format is given to the patient or in the case of a minor or incompetent adult to a parent or care giver. The "plan of care and treatment plan" -- "the baton" -- is reviewed with the patient, parent and/or family before the patient leaves the hospital.

- Inpatient to ambulatory outpatient (clinic physician) -- for patients who are seen at SETMA, the "the baton" is created in the EHR and is immediately accessible to the follow-up SETMA provider. The provider is alerted by appointment when he/she is to see the patient and that the "baton" is available for review.

- Inpatient to ambulatory outpatient (follow-up call) -- after the Hospital Care Summary and Post Hospital Plan of Care and Treatment Plan (HCSPHPCTP) is completed, a template is completed and sent to the Department of Care Coordination. This template is in the EHR where the HCSPHPCTP also resides. Both are immediately accessible to the Department. The "follow-up call from the hospital" call request is delayed for one day so that the call is made the day after the patient leaves the hospital.

- Emergency Department to ambulatory care -- the same process as in "1" above.

- Inpatient to Nursing Home -- the "baton" with a special set of Nursing Home orders is given to the patient or family and a copy is sent to the Nursing Home with the transportation to the Nursing home.

- Inpatient to Hospice -- the same as with number "6"

- Inpatient to Home Health -- the same as number "5" and "6" above. If the patient is seeing SETMA's home health, they have access to SETMA EHR and thus to the "baton."

- Inpatient to outpatient out of area -- "Baton" given to patient and family and also posted to web portal and HIE. Token sent to health provider in remote area which allows one time access to this patient's information.

With this infrastructure and with these care coordination, continuity of care and patient support functions, SETMA is ready to make a major effort to decrease preventable readmissions to the hospital.

|