|

Health Affairs published an article entitled, “Patient and Family Engagement: A Framework For Understanding The Elements And Developing Interventions and Policies.” (Health Affairs Feb 2013 vol. 32, 2 223-231l; http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/2.toc) This article provides significant insight into changing roles of patients and providers in the “new structures” of healthcare delivery, such as patient-centered medical home, accountable care organizations and others.

Compliance and Adherence

As the science of medicine increasingly identified effective treatments for preventive medicine and for chronic disease management, healthcare providers and policy makers became increasingly frustrated by the inability to translate science into outcomes. Often, patients were labeled as “non-compliant,” which commonly was the explanation for the disconnect between the science, which proved that certain interventions worked, and the practice, which was unable to reproduce the research results in patient experience. “Non-compliance” meant that patients did not follow the treatment plan which was given to them by their healthcare provider. The formulation of this last statement is at the root of the problem.

This concept of “compliance” and non-compliance” is deeply rooted in the healthcare system. The ICD-9 code list (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) used by healthcare providers to document diagnoses includes multiple codes for “non-compliance.” While the concept of “adherence” is found in the ICD-9 code, it is only as a synonym for “compliance.” In the ICD-10 code list, set to be adopted in the United States in 2014, and which was designed to provide more clarity and granularity to diagnoses includes codes for “non-compliance.” In 2015, healthcare providers will be required to adopt a diagnoses- description system known as SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature Of Medicine Clinical Terms). SNOMED, which along with ICD-10, is intended to create precision in designating diagnoses also includes “non-compliance in therapeutic regimen,” as an explanation for treatment failure.

Nowhere, however, in ICD-9, ICD-10, or SNOMED, is there a code or term for “inadequate provider explanation,” “inadequate patient education,” or “poor provider-patient communication.” Clearly treatment failure is looked upon as a patient behavior failure. Yet, there also is, in our current system, little accountability for patients who do not participate in their healthcare or who adopt behaviors which are adverse to their care. The solution which is suggested by this article and others, is that if patients are going to be held accountable for the outcomes of healthcare, and if they are going to held accountable for adverse behaviors, they must also be invited to participate in the process of healthcare both as to content and design.

The problem with “compliance” is that it means to “meet rules or standards.” It is an authoritarian approach to human behavior, which does not work very well. Often such an approach can cause resistance and can frustrate otherwise excellent care recommendations. Increasingly, healthcare providers and policy makers are addressing patient response to healthcare plans in terms of “adherence,” which means a willful adoption of a standard or a rule.

“Compliance” and “adherence” are often used as synonyms but there is a difference between the two. In healthcare, “compliance" literally means following (or complying with) doctor's recommendations. It implies a paternalistic role for the physician and a passive role for the patient. In truth, the best outcomes appear to result from an informed partnership between the patient and the physician, and the active involvement of, and communication between, both parties is what most often seems to lead to good outcomes. The dynamic of that partnership is best addressed in terms of “adherence” to mutually agreed upon treatment plans and plans of care.

In a 2010 article in the Journal Geriatric Nursing, the following contrast between “compliance” and “adherence,” appears:

“Medication adherence is a complex phenomenon. As individuals assume greater responsibility for, and participation in, decisions about their health care, teaching and supporting adherence behaviors that reflect a person's unique lifestyle are the essence of a clinician-patient partnership-and it is a perfect fit with assisted living communities and nursing practice. The notion of compliance is an outdated concept and should be abandoned as a clinical practice/goal in the medical management of patient and illness. It connotes dependence and blame and does not move the patient forward on a pathway of better clinical outcomes.”

There is one place where “compliance” and “adherence” are used distinctively and are equally valid. In measuring patient conduct and/or behavior, SETMA uses both terms. We use “compliance’ as establishing the standard of patient participation and “adherence” is an assessment of patient participation in their care. Obviously, we are using these concepts as jargon and not in their generally accepted definitions. This usage allows us to establish a standard and then to engage patients in the behavior or conduct to which they have agreed.

It is this tension between “compliance” and “adherence,” and the complex and difficult task of healthcare providers and healthcare recipients moving from “compliance” to “adherence as a standard of collegiality and collaboration, which the Health Affairs article addresses. In the abstract of the article, it is stated: ”Patient and family engagement offers a promising pathway toward better-quality health care, more-efficient care, and improved population health.”

Patient engagement and adherence may soon be found to be the process and the outcome of the interaction between provider and patient. If a metric were defined to measure patient engagement, it would be defined in terms of the process through which the provider and patient interact to form a “healthcare alliance”. A metric to measure the outcome of that alliance would be defined in terms of “adherence,” and any metric designed to measure that outcome would be described in terms of “adherence.”

Patient Engagement

Addressing the importance of patient engagement the authors quoted other sources:

“‘Patient engagement has been called a critical part of a continuously learning health system’, ‘a necessary condition for the redesign of the health care system’, the ‘holy grail’ of health care, and the next ‘blockbuster drug of the century’.”

The concept of a “continuously learning health system” is not developed in this article, but it is illustrated. As stated by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline, “continuously learning” is not so much defined by the “taking in of more information,” but it is the “changing of one’s mind” about the structures and systems which leverage change in the processes and outcomes of healthcare delivery. It is this kind of learning we are pursuing in understanding “patient engagement.” While giving the healthcare community theories about healthcare delivery redesign, the authors also have given us practical descriptions and guidelines for how to implement patient engagement.

Definitions

Definitions and understanding of the concepts of this redesign are inextricably related. The authors stated: “Adding to the confusion, the term patient engagement is also used synonymously with patient activation and patient- and family-centered care. Although the concepts are related, they are not identical” If healthcare providers are going to be able to make the transition from expecting “compliance” on their clients part, to the experience of patients “adhering” to a mutually agreed upon healthcare plans of care, it is imperative that we understand the vocabulary.

- “Patient activation-an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence for managing his/her own health and health care -- is one aspect of an individual’s capacity to engage in that care. But this term does not address the individual’s external context, nor does it focus on behavior.

- “Patient- and family-centered care is a broader term that conveys a vision for what health care should be: a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate)’ to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care.

- “...Patient and family engagement as patients, families, their representatives, and health professionals working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system-direct care, organizational design and governance, and policy making-to improve health and health care. Although we use the term patient engagement for simplicity’s sake, we recognize that those who engage and are engaged include patients, families, caregivers, and other consumers and citizens.”

With these definitions, we can begin to design activities which support the processes they identify. The authors then identify circumstances which are driving patient engagement:

- “First, work related to patient- and family-centered care and shared decision making both reflects and accelerates the shifting roles of patients and families in health care as they become more active, informed, and influential.

- “Second, a growing body of evidence suggests that patient engagement can lead to better health outcomes, contribute to improvements in quality and patient safety, and help control health care costs.

- “Third, virtually every discussion about the US health care system begins by noting that spending is spiraling upward while quality lags behind. In the search for solutions, gaining ground is the belief that patients are at the core of our system and, as such, are part of the solution.”

Similarities to Healthcare Reform and Healthcare Transformation

In many ways, patient engagement, patient activation, and patient centeredness, which all lead to patient adherence as contrasted with the coercive nature of the concept of compliance, are not unlike the dialectic between healthcare reform and healthcare transformation. Healthcare reform, similar to patient compliance, comes from the external pressure of rules, regulations and requirements. Healthcare transformation, similar to patient adherence comes from internalized ideals which become a personal passion. Ideals voluntarily adopted create a tension between the current state of affairs and the goals of the ideal. That tension creates a transformative energy which is therefore self sustaining and generative.

Exhaustion in healthcare delivery results from providers trying to “drive” the patient to good health. This is the “old system” where the provider was the “constable” attempting to impose health upon the patient. When the patient is engaged and activated by patient-centric care, the patient joins the provider in driving the healthcare process to excellence. This is the “new system” where the patient and provider are colleagues, working together for common goals and outcomes.

A Multidimensional Framework

Most helpful in this article, the authors describe a “multidimensional framework” for patient engagement. Even at the practice level this framework is helpful. Particularly of value is the realization that all elements of this framework are not appropriate in all clinical situations.

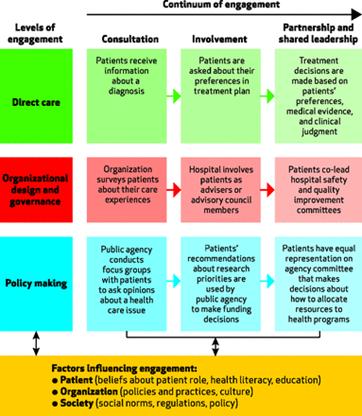

The following exhibit and the explanation which follows is as it appears in the Health Affairs article and is the work of the authors. Review of this exhibit and of the authors’ explanation is very helpful in the practical design of patient engagement strategies at the provider and practice level.

The Continuum Of Engagement

“Patient engagement can be characterized by how much information flows between patient and provider, how active a role the patient has in care decisions, and how involved the patient or patient organization becomes in health organization decisions and in policy making. At the continuum’s lower end, patients are involved but have limited power or decision-making authority. Providers, organizations, and systems define their own agendas and then seek patients’ input. Information flows to patients and then back to the system.

“At the continuum’s higher end, engagement is characterized by shared power and responsibility, with patients being active partners in defining agendas and making decisions. Information flows bidirectionally throughout the process of engagement, and decision-making responsibility is shared.

“Consider this example concerning patients’ electronic health records. At the consultation end of the engagement continuum, clinicians may use the records to provide information to patients-such as printouts of lab results-but patients cannot access the information directly. At the midpoint of the continuum, involvement, patients have direct access to their records, including notes from clinicians and the health care delivery system, but they cannot contribute or correct information.

“In contrast, at the partnership end of the continuum, patients have direct access to their records, are able to see notes from clinicians and the system, and can add or edit information. The record reflects the entire experience of care from the perspectives of both the patient and the clinicians, and care decisions can be made collaboratively, with all relevant information included.

“In describing patient engagement in terms of a continuum, we are not suggesting that the goal is always to move toward engagement at the higher end of the continuum. Such engagement is not necessarily better for every patient in every setting. Clinicians, delivery systems, and policy makers cannot assume that patients have certain capabilities, interests, or goals, nor can they dictate the pathway to achieving patients’ goals. However, the range of opportunities along the continuum is best determined based on the topic at hand and defined and created with patients’ participation.

“But even if greater engagement is not ideal for all people in all situations, more and more patients will want-even demand-greater involvement in care and policy decisions. With shared power and responsibility comes the potential for better, more patient-centered outcomes. For example, recent work related to patients with cardiac arrhythmia shows that patients who experienced shared decision making chose far less invasive treatments compared to those who did not.”

Proviso

Because the healthcare record is not only a care document but a legal document, the system to which patients are contributing materials and/or to which they are “correcting” the contributions of others, must be able to track and document the source of all entries and/or corrections. These requirements are already a part of HIPPA and of security standards for EMRs.

In the case of patient additions or corrections; the corrections must be added to the record with clear denotation of the source of the corrections. They should not replace information unless it is demonstrably proved to be factually in error. Even then, the correction must retain the original entry with the correction noted. If the record falls under legal or administrative scrutiny, it will be imperative to be able to produce the original, the correction, and the rationale for the correction.

Conclusion

Practices committed to healthcare transformation will continue to grapple with patient activation, engagement and patient-centeredness. Ultimately, these problems will be solved by generational changes in healthcare education, collaboration, and team work between healthcare professionals of all descriptions and patients who have a common goal: improved care, improved health and decreased cost.

|