|

Once you acknowledge the opioid epidemic and realize that only 27% of opioid prescriptions are taken by the person for whom the medication is prescribed, and after you address the misdirection of opioid medications, the next step, really the simultaneous needed solution, to solving the opioid epidemic is the improving of record keeping for the use of opioid medications.

How will better record keeping decrease the abuse of opioids?

- First, opioid treatment should only be allowed if the prescriber has a complete medical treatment plan which will be found in a permanent record system which reflects a patient’s total care.

- Second, the opioid treatment record should document ALL medication, not just opioids.

- Third, opioid treatment should reflect the reason for chronic or acute pain management; this will be in the form of a chronic condition diagnosis which supports chronic pain and/or a plan of care and/or treatment plan which documents the reason.

- Fourth, in his book, Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare: Theory and Practice, Admiral William McRaven (Admiral, US Navy Retired) identifies six special operations principles all of which are relevant to record keeping required for decreasing the abusive use of opioids.. They are simplicity, security, repetition, surprise, speed and purpose. No doubt the application of these principles is different in a military operation but there is no doubt that “war” on the opioid epidemic and opioid abuse give credence to the application of these principles to this topic.

- Fifth, the provider should be able to monitor and audit his/her own prescribing of opioids. Often, the realization of how frequently a provider is prescribing these medications will cause them to reconsider their prescribing habits.

- Sixth, the provider should have access to a history of all prescribed medications from all providers which are being used or which have been used by the patient.

- Seventh, in Texas, before opioids are renewed or initiated physicians should check the patient's controlled substance prescription history through the Texas Department of Public Safety's (DPS') new secure online Prescription Access in Texas (PAT) database. The program – designed to reduce patients' prescription drug abuse – allows physicians and police to go online to see what controlled substances a patient has been prescribed in the past year.

We will begin with number four. While the details and specifics of the Theory and Practice of Special Forces Warfare differ for health care and the “fight” against opioid abuse, there are parallels. Here are the six principles and how they apply to the solving of the opioid epidemic.

- Simplicity – ease of access to opioids is not essentially the cause of the problem and the solution to the epidemic is that we want to make the solution easier to use. Making the solution simpler is more important than making the use of opioids more complicated. As a principle, we want “to make it easier to do it right than not to do it at all.” If a patient should not have opioids, they should be told so; placing barriers in the way of obtaining opioids is not a reasonable way of controlling access to this class of drugs.

- Security – while the solution should be simpler, its design must make certain that no one can prescribe addictive medications without a license and that prescriptions cannot be altered, misdirected or fraudulently created.

- Repetition – the more a provider uses this solution, the easier it becomes to use such that what once took an hour can now be done in 15-30 seconds. If the tool or solution is the right solution, the more often and the longer a provider uses a tool it will become easier to use.

- Surprise -- when a patient is attempting to misdirect and/or fraudulently obtain opioids the confronting of them at the point of service with the information from number six and seven above is shocking. When all current and past prescriptions for opioids are subject to review by all providers at the point of care in the presence of the patient, before a new prescription is issued, the potential for abuse is greatly reduced.

- Speed – Simplicity and speed are two aspects of the same element of this purpose. The less time it takes for a provider to use these tools the more likely they are to be used and the more likely they are to be effective.

- Purpose -- safety and quality of care are the purposes of the appropriate use of opioids; if a patient is obtaining and using opioids appropriately, they should be as easy to obtain as any other drug

Self Auditing of Prescribing of Opioids

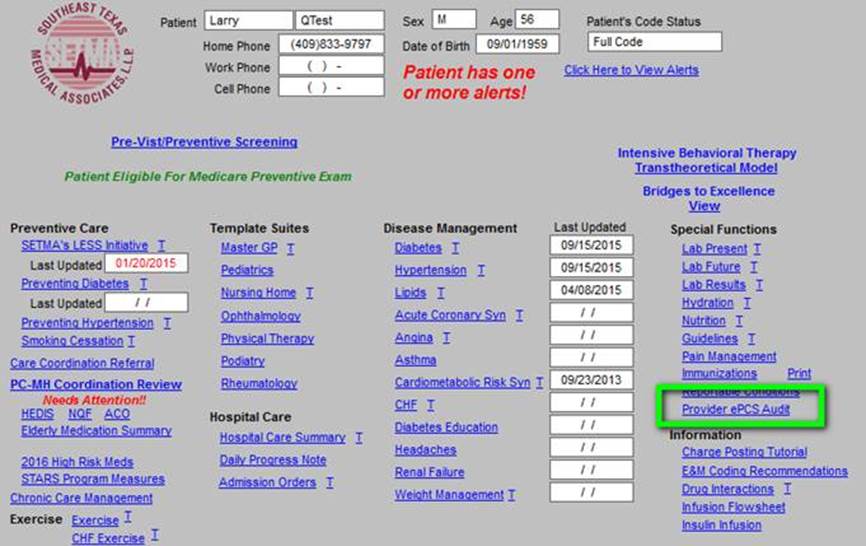

The legal process of Electronic Prescribing of Control Substances and/or opioids ( ePCS) requires that the provider is able to audit their own prescribing of these drugs. To meet this requirement, SETMA designed and deployed an auditing tool which allows each provider, at the point of service, to review all e-prescribed controlled substances they have created in the last 30, 60, 90 or 180 days. The following is a screen shot of how the new auditing tool is accessed in SETMA’s EMR. (See the button outlined in green below.) This screen is where every visit with every patient at SETMA begins.

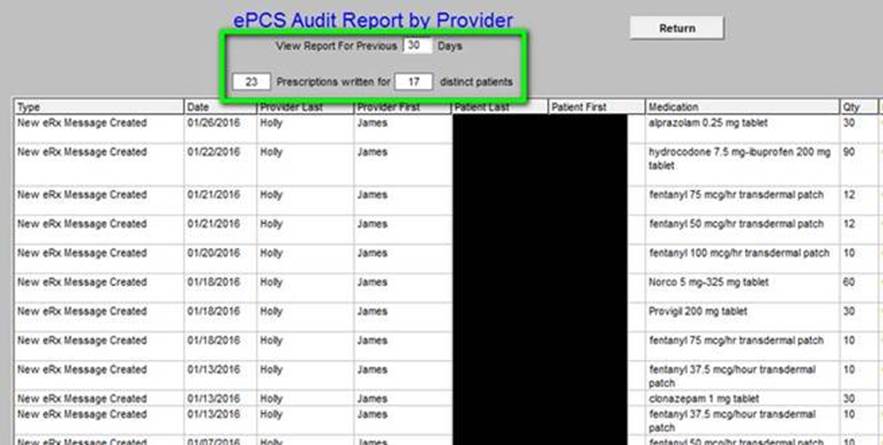

The following is a real example - de-identified - of an audit of a real ePCS for a 30-day period. Several things are worth noting:

- The time frame is selected by the provider (30,60,90, 180, days)

- The audit gives you the essential information about the prescriptions

- The audit also tells you how many medications you have ePCS and how many discreet patients that represents.

- The provider can only audit his/her own use. SETMA’s systems manager can audit all use. In fact, a number of years ago, such an audit disclosed that one provider’s prescribing of controlled substances was five times greater than all other providers. This allowed corrective action through counseling and monitoring to resolve the problem.

- In that the auditing is done at the point of service, compiling information for all patients seen by a particular provider, and in that the audit is compiled while the provider is working in a patient’s chart, this audit is created but not recorded so as not to violate HIPAA when a medical record is copied for external use.

This audit, which takes about two seconds to perform, tells this provider that in the past thirty days, he has prescribed 23 controlled substances for 17 unique patients. The audit also tells the provider:

- Type of prescription, i.e., new or refill?

- When the prescription was sent?

- Who prescribed the drug?

- What patient the prescription was for?

- What was prescribed?

- How many pills were prescribed?

- How many refills were given?

- The directions given to the patient for how to take the medication?

Again, several HIPAA issues are worth noting:

- This information is not saved to the chart. The reason is that if it were, Personal Health Information (PHI) for multiple patients would be put on a chart note which could be and would be sent to others, thus violating HIPAA.

- There is no link or computer footprint created. When the chart is closed all evidence of this audit disappears completely and permanently.

In our next part of this series, we will address the “medication history,” medication reconciliation and the use of the “surprise” tools for patient care.

|