|

This review examines SETMA’s work over the last twenty years and how it anticipated the categories of the MACRA and MIPS. While I personally like MACRA and MIPS, there are elements of its design which perpetuate past healthcare reform design flaws. This series examines those flaws and recommends means of resolving them.

The four categories defined by MIPS in 2015 correlate with the four strategies SETMA defined in 2000-2005 for the transformation of our practice. In 2000-2005, SETMA established the belief that the key to the future of healthcare transformation was an internalized ideal and a personal passion for excellence rather than reform which comes from external pressure. Transformation is self-sustaining, generative and creative. In this context, SETMA believes that efforts to transform healthcare may fail unless four strategies are employed, upon which SETMA depends in its transformative efforts.

On October 6, 2016, I realized that SETMA’s four strategies correlate with CMS’ four categories for the determination of MIPS’ Composite Performance Score. In bold face below, SETMA’s four strategies for healthcare transformation are listed; following that in red are the MIPS categories which correlate with SETMA’s strategies.

SETMA’s Strategies for Healthcare Transformation - MIPS Categories of Scoring System

- The methodology of healthcare must be electronic patient management - MIPS Advancing Care Information (an extension of Meaningful Use with a certified EMR)

- The content and standards of healthcare delivery must be evidenced-based medicine - MIPS Quality (This is the extension of PQRI which in 2011 became PQRS and which in 2019 will become MIPS -- evidence-based medicine has the best potential for legitimately effecting cost savings in healthcare while maintaining quality of care)

- The structure and organization of healthcare delivery must be patient-centered medical home - MIPS Clinical Practice Improvement activities (This MIPS category is met fully by Level 3 NCQA PC-MH Recognition).

- The payment methodology of healthcare delivery must be that of capitation with additional reimbursement for proved quality performance and cost savings - MIPS Cost (measured by risk adjusted expectations of cost of care and the actual cost of care per fee-for-service Medicare and Medicaid beneficiary)

This is remarkable both in affirming our work over the past twenty years and affirming the rationale behind MACRA and MIPS. This realization came as the result of the writing of this article and twelve other articles about MACRA and MIPS.

Personally, I approve of MACRA and MIPS and think it is a step in the right direction, however, I think there are potential problems with the design of MIPS. Some of the rationale for my concerns are present in at the following link: SETMA’s Model of Care Patient-Centered Medical Home: The Future of Healthcare Innovation and Change. The following is an explanation of this concern.

Potential Hazard of MACRA and MIPS

The most difficult thing about the new program is that there is not an absolute standard against which healthcare providers will be measured. Provider evaluation will always be a judgment made two years after the fact, I.e., you will practice and perform in 2017, but it will be 2019 before you know where you stand.

The biggest problem with this moving target is that you have to assume that everyone's results mean the same performance. That is not necessarily the case. It is possible that if everyone began to perform at a high standard that the distribution would be very narrow. The possibility exists that a person could be performing at a 95% level and still be a standard deviation below the mean which could result in a penalty for a performance which everyone would consider excellent.

Larger organizations and/or duplicitous organizations (the two are not synonymous) can find or use methods which meet the standard without achieving the excellence of care implied by the measurement. The possibility of organizations focusing on intentionally meeting a few metrics could result in a high level of performance on this artificial metric without a significant improvement in care or outcomes. This concern was present twenty years ago when SETMA began designing our “model of care.”

Core of SETMA’s Principles Not Adopted by MACRA and MIPS

At the core of SETMA’s four strategies described above is the belief and practice that one or two quality metrics will have little impact upon either the processes or the outcomes of healthcare delivery, and, they will do little to reflect quality outcomes in healthcare delivery. In the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mandatory Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), which in 2011replaced the voluntary Physicians Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) healthcare providers are required to report on nine quality metrics of the providers’ choice, but this requirement will be reduced to six quality metrics under MIPS in 2019.

SETMA argues that this is a minimalist approach to providers quality reporting and is unlikely to change healthcare outcomes or quality. The following discussion gives more detail about this assertion.

SETMA currently tracks over 200 quality metrics, but this number does not tell the whole story. SETMA employs two definitions in our use of quality metrics in our transformative approach to healthcare:

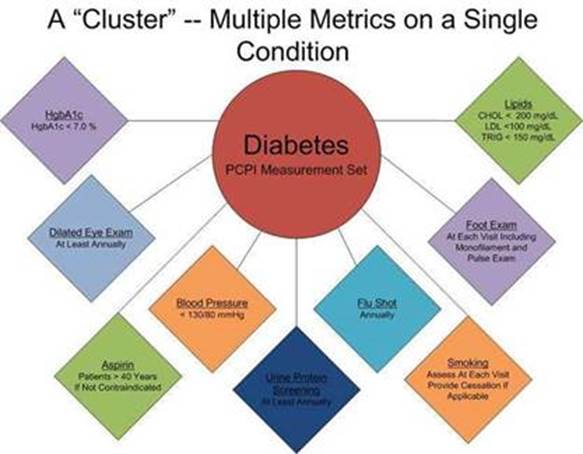

- A “cluster” is seven or more quality metrics tracked for a single condition, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, etc.

- A “galaxy” which is multiple clusters tracked in the care of the same patient, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, lipids, CHF, etc.

SETMA believes that fulfilling a single or a few quality metrics does not change outcomes, but fulfilling “clusters” and particularly “galaxies” of metrics, which are measurable by the provider at the point-of-care, can and will change outcomes. The following illustrates the principle of a “cluster” of quality metrics. A single patient, at a single visit, for a single condition, will have eight or more quality metrics fulfilled, which WILL change the outcome of that patient’s treatment.

But the “real” leverage comes when multiple “clusters” of quality metrics are measured in the care of a single patient who has multiple chronic conditions. The following illustrates a “galaxy” of quality metrics. A single patient, at a single visit, with multiple “clusters” involving multiple chronic conditions thus having 60 or more quality metrics fulfilled in his/her care, which WILL change the quality of outcomes and which will result in the improvement of the patient’s health. And, because of the improvement in care and health, the cost of that patient’s care will inevitably decrease as well. The following illustrates a “galaxy.”

SETMA"s model of care is based on the four strategies described above and on the concepts of “clusters” and “galaxies” of quality metrics. Foundational to this concept is that the fulfillment of quality metrics is incidental to excellent care rather than being the intention of that care.

MIPS and SETMA - Public Reporting

In 2008, SETMA adapted Business Intelligence software to be able to analyze and report provider performance on hundreds of quality metrics. Beginning in 2009, those reports were posted by provider name on SETMA’s website. At the writing of this article, there 7 ¾ years of results by provider name posted at www.jameslhollymd.com link: http://jameslhollymd.com/public-reporting/public-reports-by-type.

Another MACRA requirement is that each physician’s MIPS composite score will be posted to the Physician Compare website, along with the physicians’ score in each of the four performance categories. This is another element of the new law which was anticipated by SETMA. Public Reporting by provider name of quality performance is an integral part of SETMA’s Model of Care as described earlier in this document.

Quality Metrics Philosophy

The potential problem with MIPS is suggested by a review of SETMA's approach to quality metrics and public reporting which is driven by these assumptions:

- Quality metrics are not an end in themselves. Optimal health at optimal cost is the goal of quality care.

- Quality metrics are simply “sign posts along the way.” They give directions to health. And the metrics are like a healthcare “Global Positioning Service”: it tells you where you want to be; where you are, and how to get from here to there.

- The auditing of quality metrics gives providers a coordinate of where they are in the care of a patient or a population of patients.

- Statistical analytics are like coordinates along the way to the destination of optimal health at optimal cost. Ultimately, the goal will be measured by the well-being of patients, but the guide posts to that destination are given by the analysis of patient and patient- population data.

- There are different classes of quality metrics. No metric alone provides a granular portrait of the quality of care a patient receives, but all together, multiple sets of metrics can give an indication of whether the patient’s care is going in the right direction or not. Some of the categories of quality metrics are: access, outcome, patient experience, process, structure and costs of care.

- The collection of quality metrics should be incidental to the care patients are receiving and should not be the object of care. Consequently, the design of the data aggregation in the care process must be as non-intrusive as possible. Notwithstanding, the very act of collecting, aggregating and reporting data will tend to create a Hawthorne effect.

- The power of quality metrics, like the benefit of the GPS, is enhanced if the healthcare provider and the patient are able to know the coordinates while care is being received.

- Public reporting of quality metrics by provider name must not be a novelty in healthcare but must be the standard. Even with the acknowledgment of the Hawthorne effect, the improvement in healthcare outcomes achieved with public reporting is real.

- Quality metrics are not static. New research and improved models of care will require updating and modifying metrics.

The Limitations of Quality Metrics

The New York Times Magazine of May 2, 2010, published an article entitled, "The Data-Driven Life," which asked the question, "Technology has made it feasible not only to measure our most basic habits but also to evaluate them. Does measuring what we eat or how much we sleep or how often we do the dishes change how we think about ourselves?" Further, the article asked, "What happens when technology can calculate and analyze every quotidian thing that happened to you today?" Does this remind you of Einstein's admonition, "Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted?"

Technology must never blind us to the human. Bioethicist, Onora O'Neill, commented about our technological obsession with measuring things. In doing so, she echoes the Einstein dictum that not everything that is counted counts. She said, "In theory again the new culture of accountability and audit makes professionals and institutions more accountable for good performance. This is manifest in the rhetoric of improvement and rising standards, of efficiency gains and best practices, of respect for patients and pupils and employees. But beneath this admirable rhetoric the real focus is on performance indicators chosen for ease of measurement and control rather than because they measure accurately what the quality of performance is."

Technology Can Deal with Disease but Cannot Produce Health

In our quest for excellence, we must not be seduced by technology with its numbers and tables. This is particularly the case in healthcare. In the future of medicine, the tension - not a conflict but a dynamic balance - must be properly maintained between humanity and technology. Technology can contribute to the solving of many of our disease problems but ultimately cannot solve the "health problems" we face. The entire focus and energy of "health home" is to rediscover the trusting bond between patient and provider. In the "health home," technology becomes a tool to be used and not an end to be pursued. The outcomes of technology alone are not as satisfying as those where trust and technology are properly balanced in healthcare delivery.

Our grandchildren's generation will experience healthcare methods and possibilities which seem like science fiction to us today. Yet, that technology risks decreasing the value of our lives, if we do not in the midst of technology retain our humanity. As we celebrate science, we must not fail to embrace the minister, the ethicist, the humanist, the theologian, indeed the ones who remind us that being the bionic man or women will not make us more human, but it seriously risks causing us to being dehumanized. And in doing so, we may just find the right balance between technology and trust and thereby find the solution to the cost of healthcare.

It is in this context that SETMA whole-heartedly embraces technology and science, while retaining the sense of person in our daily responsibilities of caring for persons. Quality metrics have made us better healthcare providers. The public reporting of our performance of those metrics has made us better clinician/scientist. But what makes us better healthcare providers is our caring for people.

How Can MACRA and MIPS Be Improved?

MIPS could be improved by the establishment of an absolute standard against which providers and practices will be measured, rather than a comparison with others. Competitiveness among providers can improve performance on objective standards but if the idea is to improve the quality of care, an established standard which everyone can meet would be better than the current design of MIPS. Please review the first part of this article for further explanation of this concept.

Additionally, the artificial assumption that performance on nine, or six, or any number of isolated, unconnected, arbitrarily metrics chosen by a practice, often on the basis of how easy it is to perform the requirements of the metric, is not going to change the quality element of practice. This was always the flaw of PQRI and subsequently PQRS, although “comprehensive metric sets” for a particular condition were an option in both programs. The design flaw was that the comprehensive metric sets were not required. Now the same mistake is being made in MIPS.

An alternative is that just as National Committee Quality Assurance (NCQA0 recognition as a Level 2 Patient-Centered Medical Home meets the MIPS’ Clinical Practice Improvement Activities, so a practice or provider meeting NCQA standards for Diabetes Recognition and for Heart/Stroke Recognition could be given credit for the metric side of the Quality Category of the MIPS Scoring System.

In addition to a recognized and established standard which represents excellence in complex, chronic care settings, the data base generated by this change to MIPS would allow for statistical analysis of the kinds of practices which are meeting standards of excellence which would allow for further public policy observations about how to improved population health. Other accreditation agencies for quality healthcare performance can also be included in this option, such as the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Healthcare, URAC and the Joint Commission.

Ultimately, the real flaw of MACRA and MIPS is that like any standard it was created to be measurable when what it needs to be is scalable and elastic to support healthcare delivery transformation rather than at best a system which promote compliance without necessarily improving care quality. This is the very nature of reform.

Additionally, the MIPS artificial assumption that performance on nine, or six, or any number of isolated, unconnected, arbitrarily metrics chosen by a practice, often on the basis of how easy it is to perform the requirements of the metric, is not going to change the quality element of practice. This was always the flaw of PQRI in 2006 and subsequently PQRS in 2011, although “comprehensive metric sets” for a particular condition were an option in both programs. The design flaw was that the comprehensive metric sets were not required. Now the same mistake is being made in MIPS.

An alternative is that just as National Committee Quality Assurance (NCQA0 recognition as a Level 2 Patient-Centered Medical Home meets the MIPS’ Clinical Practice Improvement Activities, so a practice or provider meeting NCQA standards for Diabetes Recognition and for Heart/Stroke Recognition could be given credit for the metric side of the Quality Category of the MIPS Scoring System.

In addition to an recognized and established standard which represents excellence in complex, chronic care settings, the data base generated by this change to MIPS would allow for statistical analysis of the kinds of practices which are meeting standards of excellence which would allow for further public policy observations about how to improved population health. Other accreditation agencies for quality healthcare performance can also be included in this option, such as the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Healthcare, URAC and the Joint Commission.

Ultimately, the real flaw of MACRA and MIPS is that like any legislated standard it was created to be measurable when what it needs to be is scalable and elastic to support healthcare delivery transformation rather than at best having a system which promotes compliance without necessarily improving care quality. This is the very nature of reform.

The Ultimate Hope of the Future of Healthcare is Transformation

To be successful, the implementation of new polices and initiatives witch will produce the future we imagine, must be transformative which comes from within. Transformation results in change which is not simply reflected in shape, structure, dimension or appearance, but transformation results in change which is part of the nature of the organization being transformed. The process itself creates a dynamic which is generative, i.e., it not only changes that which is being transformed but it creates within the object of transformation the energy, the will and the necessity to sustain and expand that change and improvement. Transformation is not dependent upon external pressure (rules, regulations, requirements) but is sustained by an internal drive which is energized by the evolving nature of the organization.

While this may initially appear to be excessively abstract, it really begins to address the methods or tools needed for reformation, or for transformation. They are significantly different. The tools of reformation, particularly in healthcare administration are rules, regulations, and restrictions. Reformation is focused upon establishing limits and boundaries rather than realizing possibilities. There is nothing generative - creative - about reformation. In fact, reformation has a "lethal gene" within its structure. That gene is the natural order of an organization, industry or system's ability and will to resist, circumvent and overcome the tools of reformation, requiring new tools, new rules, new regulations and new restrictions. This becomes a vicious cycle. While the nature of the system actually does change, where the goal was reformation, it is most often a dysfunctional change which does not produce the desired results and often makes things worse.

The tools of transformation may actually begin with the same ideals and goals as reformation, but now, rather than attempting to impose the changes necessary to achieve those ideals and goals, a transformative process initiates behavioral changes which become self-sustaining, not because of rules, regulations and restrictions but because the images of the desired changes are internalized by the organization which then finds creative and novel ways of achieving those changes.

It is possible for an organization to meet rules, regulations and restrictions perfunctorily without ever experiencing the transformative power which was hoped for by those who fashioned the external pressure for change. In terms of healthcare administration, policy makers can begin reforms by restricting reimbursement for units of work, i.e., they can pay less for office visits or for procedures. While this would hopefully decrease the total cost of care, it would only do so per unit. As more people are added to the public guaranteed healthcare system, the increase in units of care will quickly outstrip any savings from the reduction of the cost of each unit.

Transformation of healthcare would result in a radical change in relationship between patient and provider. The patient would no longer be a passive recipient of care given by the healthcare system. The patient and provider would become an active team where the provider would cease to be a constable attempting to impose health upon an unwilling or unwitting patient. The collaboration between the patient and the provider would be based on the rational accessing of care. There would no longer be a CAT scan done every time the patient has a headache. There would be a history and physical examination and an appropriate accessing of imaging studies based on need and not desire.

This transformation will require a great deal more communication between patient and provider which would not only take place face-to-face, but by electronic or written means. There was a time when healthcare providers looked askance at patients who wrote down their symptoms. The medical literature called this la maladie du petit papier or "the malady of the small piece of paper." Patients who came to the office with their symptoms written on a small piece of paper where thought to be neurotic.

No longer is that the case. Providers can read faster than a patient can talk and a well thought out description of symptoms and history is an extremely valuable starting point for accurately recording a patient's history. Many practices with electronic patient records are making it possible for a patient to record their chief complaint, history of present illness and review of systems, before they arrive for an office visit. This increases both the efficiency and the excellence of the medical record and it part of a transformation process in healthcare delivery.

This transformation will require patients becoming much more knowledgeable about their condition than ever before. It will be the fulfillment of Dr. Elliot Joslin's (The founder of the Diabetes Center of Excellence in Bosom, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical College) dictum, "The person with diabetes who knows the most will live the longest."

It will require educational tools being made available to the patient in order for patients to do self-study. Patients are already undertaking this responsibility as the most common use of the internet is the looking up of health information. It will require a transformative change by providers who will welcome input by the patient to their care rather seeing such input as obstructive.

This transformation will require the patient and the provider to rethink their common prejudice that technology - tests, procedures, and studies - are superior methods of maintaining health and avoiding illness than self discipline, communication, vigilance and "watchful waiting." In this setting, both provider and patient must be committed to evidence-based medicine which has a proven scientific basis for medical-decision making. This transformation will require a community of patients and providers who are committed to science. This will eliminate "provider shopping" by patients who did not get what they want from one provider so they go to another.

This transformation will require the reestablishment of the trust which once existed between provider and patient to be regained. The restoration of trust between the provider and patient cannot be created by fiat. It can only be done by the transformation of healthcare in to system which we had fifty to seventy-five years ago. With that trust relationship coupled with modern science, healthcare can produce a new dynamic which we call patient-centered medical home. In this setting the patient must be absolutely confident that they are the center of care but also they must know that they are principally responsible for their own health. The provider must be an extension of the family. This is the ultimate genius behind the concept of Medical Home and it cannot be achieved by regulations, restrictions and rules.

The transformation will require patient and provider losing their fear of death and surrendering their unspoken idea that death is the ultimate failure of healthcare. Death is a part of life and, in that, it cannot forever be postponed, it must not be seen as the ultimate negative outcome of healthcare delivery. While the foundation of healthcare is that we will do no harm, recognizing the limitations of our abilities and the inevitability of death can lead us to more rational end-of-life healthcare choices.

Conclusion

MIPS is a good thing; it could be better and the ideas contained in this series would help make it better.

|